Editor’s Note: Article 6 of the Paris Agreement states that countries are to set up a global carbon market to encourage a more affordable transition towards carbon neutral economies. The implementation of the article was a major focus of COP25 – Read what our fellows have to say about it below!

Top Down and Bottom Up: The Dual Approach Needed to Address Climate Change – Lauren Pawlowski

Article 6 Deconstructed and Why No One Can Agree on a Solution – Hope Dymond

Carbon Pricing and Indigenous People: Key Issues at COP25 – Michael Goccia

Top Down and Bottom Up: The Dual Approach Needed to Address Climate Change

Lauren Pawlowski – B.A. Environmental Studies and B.S. Economics

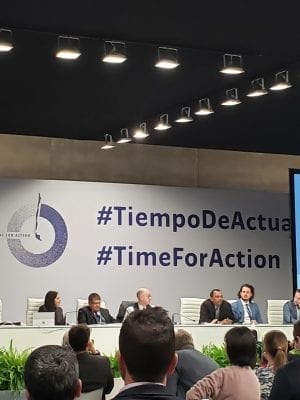

A lot of the conversation and debate at COP25 was about carbon markets, carbon budgets, and renewable energy. There was heated talk in some of the high-level negotiations between country delegates regarding consensus on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement which is centered on carbon markets.

These negotiations were only in one or two hour blocks and these high-status delegates only meet at the annual COP in December, in June, and at a few interim meetings during the year. Also, unless every country in attendance agrees, nothing gets passed, so I could clearly see the frustration of delegates over this lengthy process when countries like Egypt prioritized their own individual interests over global cooperation.

These types of international agreements and articles of the Paris Agreement are important in building a foundation of environmental policy on a global scale. However, it seems like a difficult task to reach consensus on and outline ways to implement these policies.

On a similar note, encouraging countries to reach their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and to reduce emissions through energy infrastructure is a good starting point for reducing climate change at the national level. However, change at the local level is more community-based, dignifying, and attainable.

Shawna Lawson, who is a part of the Indigenous Environmental Network, Native Movement.org, and is Ahtna on her father’s side and Supiaq on her mother’s side,, mentioned at a panel that Native Americans have the highest rates of breast cancer, diabetes, incarceration, and suicide in Alaska. She talked about how DDT is still used in other countries besides the US today, so it biomagnifies in the global aquatic food chains and causes health problems within the tribes.

When I asked her how she tries to alleviate these social and environmental justice issues, she highlighted the importance of education and culture. Shawna said that in her traditional language, “there is no way to say ‘I love you’ or ‘I’m sorry.’ You have to show it.” In this sense, the tribes have to honor their responsibility to the earth through their daily actions and by passing on their cultural values through songs, stories, and teachings.

She talked about her tribe when she said, “We made an agreement to take care of the earth and the earth, in agreement, would take care of us.”

Through their indigenous way of life that honors the planet and its natural resources, they are environmental stewards. Shawna also told us how there are only two Alaskan tribal schools that educate indigenous people on the true history of US involvement in the tribal nations and colonization. By passing down stories of life before big oil extractors took over their lands, she said, they are able to take pride in their culture and ties to their environment.

In terms of the climate crisis, Shawna told the crowd that she worries about everyone else in the world. Her tribe, she said, “Will continue to be here. We will figure it out.”

This is one of many examples where bottom-up efforts to make a community more sustainable are best achieved through storytelling, activism, spreading awareness, and local policy change. This makes big issues like climate change and environmental justice more personal and relatable and it enables small individual actions to contribute to greater world change.

Environmental issues must be tackled from these two lenses: one from a technology, infrastructure, economic lens and one from a social change perspective. International, national, and local change all need to occur simultaneously in order for the world to tackle the climate crisis, but more individuals can contribute to this through action in the local communities that they know best. In this way, communities can honor their experiences and culture and fight for a better future together.

Article 6 Deconstructed and Why No One Can Agree on a Solution

Hope Dymond – B.S. Environmental Engineering

My first blog post was about Article 6, and I would recommend reading that (see Hope Dymond) first, as well as Alyssa Pagan’s Article 6 blog, to get a full understanding of this important component of this year’s negotiations.

Now that we have returned home, and the COP 25 has concluded, what is the status of Article 6? Let’s see if we can find out.

At the conference, it is impossible to be at every negotiation at once, and for a newcomer, even if I was at every negotiation I would falter in comprehending what was going on. However, I found a helpful tool at the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s booth in Madrid. They write a Bulletin (check it out!) for each day of the conference that summarizes the goings-on of the party talks. From here is where we’ll look to see the failings of the COP in regards to Article 6, and details on what is next.

The COP ended Sunday December 15, two days after the official deadline of December 13th. And yet even with the extra time, regarding Article 6, “CMA President Schmidt reported no substantive agreement could be reached on this agenda item.”

The countries could not agree.

There were issues on specifics of Article 6 that countries held differing views on, and even after the two week conference the decisions could not be made.

One outstanding issue was whether carbon credits, or units, from the previous Kyoto Protocol could be used to in this new trading system under the Paris Agreement’s Article 6. Countries such as Australia and Brazil were proponents of this happening, but many other countries, as well as NGOs, called for the avoidance of double counting.

My understanding of the logic behind both sides is not that advanced, but it goes like this: If I am an Australian and I have spent lots of money reducing emissions in a certain sector, then suddenly I’m being told I can’t use my hard earned “credits” in a new carbon trading scheme, then I am being denied a reward for all my work.

On the opposing side, against double counting, is the bathtub argument from my first blog post. The millions of carbon credits put towards previous trading schemes such as the Kyoto scheme are called “hot air” because counting them again in the new trading system will flood the carbon market. You have probably heard what flooding any market will do –flooding will bring the prices way down and low prices make carbon markets ineffective.

To the groups standing firmly against double counting, these “hot air” credits need to be avoided. The negotiations on this topic were pushed to June 2020 where the SBSTA (another fun acronym meaning Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice) will discuss further.

One more problem the countries couldn’t agree on was human rights. Some parties wanted to explicitly mention human rights in Article 6, other wanted to include “other rights”.

An example to help illustrate the consequences was brought up at a side event on a “Just Transition”. If Brazil sells a carbon credit of 1000 tonnes of carbon (let’s just use pretend units) to France, then France can emit 1000 tonnes of carbon into the air and in theory it is is “zero sum game”; France can report on its NDC that it did not emit those thousand tones because it bought the credit from Brazil.

But what actually happened in Brazil? If the carbon credit took the form of funding a renewable energy project that sounds pretty cool. All good things, right? Not always.

There are a substantial number of reports of renewable energy companies displacing indigenous people to build wind or solar farms. Read this article for information on native leaders in Honduras that have been killed in the struggle for their land, and to have free and open consent with incoming industry.

Fossil fuel and other extractive industries have done this for many years, but it is important to know that renewable development is not inherently people-conscious. An Article 6 that lacks provisions for human rights can secretly accelerate the endangering of those most vulnerable, while appearing to be beneficial.

Last year’s COP24, in Katowice, had not found agreement on the carbon trading system. Now, with another year and no conclusion, it is difficult to find optimism. However, the COPs will continue, as well as the many meetings that bring together the negotiating bodies and advisors year round.

Some countries may begin their own carbon trading systems in light of the progress that has been made at this year’s conference. As an observer, I feel my own disappointment that must pale in comparison to the frustrations felt by delegates that have worked for months only to turn up without a conclusion.

I think the only reasonable next step for us students and citizens is to learn as much as we can about these systems that are being proposed, such as Article 6. My most exhilarating experiences in the negotiating rooms were the ones where I realized I actually knew what the delegates were talking about, versus the times where I scanned the paragraphs being discussed over and over and still could not for the life of me comprehend.

It is important for us to be literate in the specifics of the conversation, such as carbon markets and carbon capture technologies. Knowing what is actually being talked about at these conferences makes me, and I hope you, less inclined to shrug it all off as toothless political babble.

Secondly, I have learned that the broader context of human rights and history needs to be understood by us. This is critical, and I think Harry Zehner’s blog post outlines the “tale of two COPs” well. At the next COP, Article 6 may actually be finalized. That gives all of us a whole other year to read up and understand what is at stake.

Carbon Pricing and Indigenous People: Key Issues at COP25

Michael Goccia – B.S. Management and Economics

My week at COP25 in Madrid has flown by. Before coming to Madrid I was apprehensive that there would not be enough to justify a whole week at the conference. I was pleasantly surprised by the variety and quantity of events to attend, making me wish we had the full two weeks to engage with more people and attend other events. I originally applied to the UConn@COP fellowship without knowing exactly what to expect at the COP. I knew there would be discussions and lots of different opportunities, but I was unsure what I would be able to attend. It was very impactful to attend the actual negotiation sessions as well as the unique side events.

My week at COP25 in Madrid has flown by. Before coming to Madrid I was apprehensive that there would not be enough to justify a whole week at the conference. I was pleasantly surprised by the variety and quantity of events to attend, making me wish we had the full two weeks to engage with more people and attend other events. I originally applied to the UConn@COP fellowship without knowing exactly what to expect at the COP. I knew there would be discussions and lots of different opportunities, but I was unsure what I would be able to attend. It was very impactful to attend the actual negotiation sessions as well as the unique side events.

The wide range of topics for side events was impressive. I was very glad we were given the freedom to pick and choose which events we would like to attend. This allowed me to tailor my UConn@COP experience to my interests. I have an economics and business background so I gravitated to events with relevant topics, but I also saw UConn@COP as a unique opportunity to broaden my horizons. It is for this reason that I attended many sessions about climate justice and the impact of climate change on indigenous people. These events, especially those relating to indigenous people, were very unique to the United Nations.

I think it would have been difficult to hear the perspective of these groups if I did not attend COP25 in Madrid. These discussions about indigenous peoples also helped me to better understand their perspective and the meaning of climate justice overall. I feel that the perspective of many indigenous groups and some countries is grounded in the context of colonization. This historical context to the climate change issue guided many groups to arrive at the conclusion that the countries who are primarily responsible for carbon dioxide emissions should be providing financial support to countries that have been disproportionately impacted by climate change.

While at COP25 I was able to listen to many conversations about what the best course of action is to adequately address climate change. In addition to the idea that some countries should be paying reparations to those who are being disproportionately impacted, there was much discussion about green investment opportunities.

One of the most informative sessions I was able to attend on this topic was called “The road to carbon pricing in emerging economies: issues and challenges.” This included discussions about carbon pricing and issues specific to emerging economies and indigenous people.

In my view, this was a key division at COP25. Climate justice proponents viewed green investment funds that expected a return on their investment as a new form of colonialism, while green fund investors viewed their approach as the most efficient way to help countries meet their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). I found this divide to be very interesting because I could see the truth to both arguments. It will be interesting to follow this discussion through the rest of COP25 and future COPs to see what the resolution will be. I think that both sides will need to compromise to reach an agreement, potentially having a blend of profitable investments in addition to gratis infrastructure projects in some nations.

Michael Goccia is a senior from Mystic, CT pursuing a dual degree in Management and Economics.