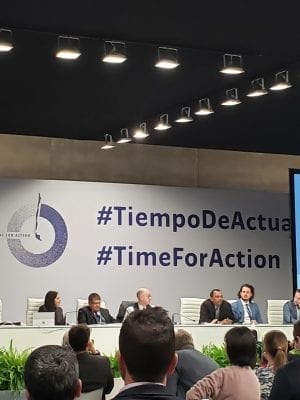

Editor’s Note: Climate change requires humans to adapt and modify their behavior to preserve natural resources for generations to come. Our fellows identified a number of natural resource issues at the COP. Some areas have shown growth in adaptation measures, but other sectors require much more work if we hope to address and adapt to climate change.

Agriculture: The Forgotten Sector and the Food Security Crisis – Georgia Hernandez-Corrales

“Help, I Can’t Breathe!” – Air Pollution and Global Health – Himaja Nagireddy

Agriculture: The Forgotten Sector and the Food Security Crisis

Georgia Hernandez-Corrales – M.S. Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

[English version]

The biggest rebellion that a community can do in the face of the current climatic crisis is secure its food independence.

One of the discussions that most impacted me at COP@25 was the issue of food security. Especially because I come from a country (Costa Rica) in which we are giant producers of pineapple, banana, and flowers. What would happen if a global catastrophe happens and we could not continue importing all our food? Would we survive with fruits and flowers?

This is the situation of many countries in the world where governments have looked away from the importance of food security. This issue was discussed in the side event on actions for future food security. Panelist Dhanush Dinesh (CCAFS) was very direct in stating that the collective imaginary is to think farming is desperate decision but should be a decision for prosperity. Unfortunately, this is how governments and society in general think about agriculture. They think agriculture is a symbol of poverty and lack of education. The irony is great when the entire population depends on this forgotten sector. Farmers are a fragile group which already has to address intrinsic problems and are more vulnerable now than ever because of climate change.

Dhanush talked about the need to transform the production system through simple steps so that governments and communities can easily adapt their production systems to better environmental practices.

Among the most important mechanisms are eliminating crop expansion and concentrating on increasing soil health, reducing food waste, and improving crops with new production technologies. He mentioned agriculture must be seen as something “cool” in order to encourage new generations of farmers that seek prosperity. Of course, this has to be coupled with a government that increases the resilience of markets and supports the social mobility of agricultural sectors. In addition, it should go hand in hand with the promotion of social change for more sustainable decision-making, such as more friendly environmental diets and reduction of food waste.

If we modify our behaviors as consumers, the market will be forced to change according to current demands. It seems that countries are not going to agree at the COP@25 negotiations, but against this, what is left is to safeguard the future through local governments. Now, the change has to begin at a very personal level, such as buying food locally, demand that local governments protect local producers and protect them from climate change and eliminate food waste. At the level of local government there must be a transfer of knowledge from universities and institutions towards production, zero agricultural land expansion, encourage agroecology, and to eliminate myths around technology that improves production.

[Spanish version]

Seguridad alimentaria para el futuro

La rebelión mas grande que una comunidad puede hacer ante la crisis actual es asegurar su independencia alimentaria.

Uno de los temas que más me impactaron en la COP@25 fue el tema de seguridad alimentaria. En especial porque vengo de un país (Costa Rica) en el que somos gigantes productores de piña, banano y flores. ¿Qué pasaría ante una catástrofe mundial y no pudiéramos seguir importando todos nuestros alimentos? ¿Sobreviviríamos con frutas y flores?

Esta es la situación de muchos países en el mundo donde los gobiernos han apartado su mirada de la importancia de asegurar la producción alimentaria nacional. Este tema se discutió en el Side Event sobre acciones para la futura seguridad alimentaria. El panelista Dhanush Dinesh (CCAFS) fue muy directo al mencionar que es inaceptable el imaginario colectivo que se tiene de que tornarse hacia la agricultura sea una decisión desesperada, sino que debería ser una decisión para la prosperidad. Lamentablemente así es como ven la agricultura los gobiernos y la mayoría de las personas en el mundo. La agricultura es símbolo de pobreza y falta de educación. Esto es irónico al pensar que toda la población depende de este sector olvidado y que ya es frágil para atender problemas intrínsecos, y aún ahora más vulnerable ante el cambio climático.

Dhanush habló de la necesidad de transformar el sistema de producción mediante pasos simples para que los gobiernos y comunidades se puedan adaptar fácilmente a sus sistemas de producción.

Entre los mecanismos más importantes están eliminar la expansión de los cultivos y concentrarse en aumentar la salud de los suelos, reducir la pérdida de comida, y mejorar los cultivos con nuevas tecnologías de producción. Mencionaba que de alguna manera hay que hacer ver la agricultura como algo “cool” para fomentarla entre las nuevas generaciones y que sea vista como un símbolo de prosperidad. Claro está, esto iría de la mano con un gobierno que aumente la resiliencia de los mercados y apoye la movilidad social de los sectores agrícolas. Además, debería de ir de la mano con la promoción de un cambio social para la toma de decisiones más sustentables, como el caso de dietas más amigables con el ambiente y una reducción del desperdicio de alimento.

Si modificamos nuestras conductas como consumidores, el mercado se verá obligado a cambiar conforme a las demandas actuales. Todo parece ver que los países no se van a poner de acuerdo en las negociaciones de la COP@25, pero ante tanta inoperancia lo que queda es salvaguardar el futuro mediante los gobiernos locales. Así que el cambio comienza a nivel muy personal, desde que compremos alimentos locales, exijamos a los gobiernos locales la protección de los productores locales para resguardarlos ante consecuencias del cambio climático, y hasta eliminar el desperdicio de comida. A nivel de gobierno local debe de existir una transferencia de conocimiento de universidades y centros de conocimiento hacia la producción, evitar la competición de productores locales con exteriores, fomentar la agroecología mediante la eliminación de monocultivos y que toda práctica esté a favor el ambiente, y finalmente, eliminar la misticidad alrededor de técnicas de mejora en la producción.

Georgia is a graduate student from the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Department at UConn.

“Help, I Can’t Breathe!” – Air Pollution and Global Health

Himaja Nagireddy – B.S. Molecular and Cell Biology, Physiology and Neurobiology, and Sociology

Far too often, we take the air we breathe for granted. A COP25 exhibit made it a point to draw attention to the air pollution that millions are experiencing on a daily basis, to help us understand why addressing air pollution is key to our fight against climate change.

The immersive art installation contained five pods which mimicked air pollution in four of the most polluted cities in the world (London, Beijing, Sao Paulo, and New Delhi), as well as one of the cleanest air environments in the world (Tautra in Norway).

The pods themselves were safe, containing perfume blends and fog machines to imitate the quality of the air at these different locations. The temperature was also controlled in the pods. A heater was added in the Delhi pod to mimic warm temperatures and an air conditioner was added to the Beijing pod to mimic the cold temperatures this time of year.

As soon as we walked into the first pod, which mimicked the air conditions of London, the decrease in air quality was clearly visible- the air was much foggier and smelled strongly. Walking into the New Delhi pod, one immediately felt the humid and sticky atmosphere of the city and the fog was a bit thicker. It was hard to see objects that were over 15 feet away with the smog. The transition into the Beijing pod was a stark temperature difference. We could see our breath turn into fog and merge with the heavy smoke in the room. The Sao Paulo pod was warmer but with a similar fog density. This lead to the last pod mimicking air quality conditions in Tautra, Norway. Here, the air was clear and smelled fresh, a welcome change from the other pods that were difficult to breathe in.

Walking through the pods put into perspective so much of what I had known but never really understood. It is one thing to read articles about air particulate matter in cities that exceed safe air pollution limits and ano ther to experience what degraded air quality feels like.

According to the World Health Organization, outdoor air pollution caused an estimated 4.2 million deaths in both urban and rural areas and has been linked to stroke, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer and acute respiratory infections.

As a student interested in understanding the intersections between health and the environment, walking through the pods helped me better understand why addressing air pollution is critical to our fight against climate change and our goal for achieving social health and well-being globally.

This is but one example of how COP25 hosted a variety of platforms for stakeholders to raise their voices in an effort to bring global climate change issues and their relevance to social health and well-being close to home. As a first time COP attendee, I walked away from the event with a strong sense of hope and personal responsibility to continue fighting the fight against climate change, to ensure a more equal and fairer world for all.

Himaja Nagireddy, from Acton, MA, is a senior undergraduate student pursuing three degrees in Molecular and Cell Biology, Physiology and Neurobiology, and Sociology with a minor in Chemistry.