Editor’s Note: Despite contributing little to climate change, indigenous groups will likely be among the first to suffer the consequences. These communities have been quick to advocate against climate change, but have struggled to make their voices heard amongst the global community.

Disproportionate Representation at COP25 – Matthew Yang

The Power of Indigenous Communities and Traditional Knowledge – Megan Ferris

Disproportionate Representation at COP25

Matthew Yang – B.S. Civil Engineering

Coming back from COP25 I’m overwhelmed with mixed emotions. On one hand I’m suffused with exuberance and a sense of fulfillment. Attending the UN Climate Change Conference was a once in a lifetime experience. I got to participate in a conference convening thousands of the world’s leading scientists, politicians, business leaders, students and activists. In Madrid I gained new experiences, insights and met genuinely inspiring people. Yet there was constantly this underlying feeling that I didn’t belong. This discomfort didn’t stem from the presence of intimidating ambassadors and overpowered prime ministers. Moresoe it came from a gradual awareness of the voices absent from COP25, the presences absent from the discussion.

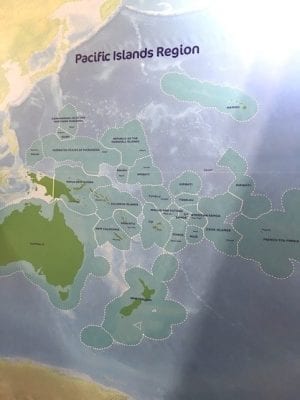

Coastal, island, and sub-saharan communities in non-western countries are disproportionately affected by climate change. I had the privilege of hearing from ambassador Ronald Jean Jumeau of Seychelles, a small island nation off the eastern coast of Africa. He fears that rising sea levels are destined to make thousands of islands like Seychelles uninhabitable. Millions of people from island nations will be forced to flee their homes, abandoning their culture, way of life, and even their language. The COP is intended to be a space for nations to negotiate and propose a unified response to the climate crisis. Despite having the most to lose, nations like the Seychelles lack the representation and political clout needed to make their problems relevant in negotiations.

Nations like the Seychelles face tremendous logistical, economic, social and political barriers just to attend the conference. The COP was originally planned for Santiago, Chile, but violent protests in the weeks before forced Chile to withdraw. Scrambling officials were able to find a replacement venue in Madrid, Spain.

Thousands of people had to try their best to reschedule flights, rebook hotels, and recuperate expenses. We were some of the fortunate, who were able to still attend the conference in Madrid. However this logistical nightmare prevented hundreds of representatives from nations like Peru from attending the COP. For those representatives able to attend, the stakes were extremely high. The livelihood of thousands of people weighed on the handful of delegates sent by these disenfranchised communities. As the negotiations carried on, many of these delegates became more and more pessimistic. It was becoming evident that little to no progress was being made.

I am extremely grateful and honored to be among the 21 delegates UCONN sent to COP25. I’m also disturbed and upset by our school having representation not afforded to entire nations and impoverished populations bearing the brunt of climate change. There is a clear disparity in representation between western and non-western countries at the UN Climate Change Conference. Climate change and global superpowers inattention to developing and at-risk nations are rooted in economic disparity and the extractive economies of the west. After disenfranchising non-western countries for centuries, it’s vital western nations listen responsively to the communities suffering from climate change. We must be able to propose solutions for all, and not just for the hegemony.

The Power of Indigenous Communities and Traditional Knowledge

Megan Ferris – B.S. Environmental Science

Reflecting on all my experiences and encounters at COP25, I have decided that one of the most powerful lessons I learned was how resilient indigenous communities are and how important their role is in mitigating and stopping global climate change.

These communities have produced the lowest amounts of carbon dioxide that have entered the atmosphere and more importantly, they have an influential tool many developed countries don’t utilize — the power of storytelling.

Most of my memories gained from COP revolved around stories I heard from various people I encountered. Stories link people and communities to each other by appealing to the emotions. Many people have a hard time understanding the complicated numbers that are involved in discussions on global climate change. However, hearing firsthand stories of how nations, islands, and people are personally being affected allows others to truly comprehend the devastation involved in this global crisis, and thus I’m hopeful these indigenous voices and their work will get more people to act.

One story that left a lasting impact on me was from the people of the Polynesian islands.

Angelica Salele, from the island of Tuvolu, told me her experiences with her island sinking and how the salt water from the seas rising has destroyed much of the vegetation on the outskirts of the islands, leaving them with less food to eat.

She also told how she was a mother and her biggest desire is to have her child know the island she has grown to love. But she fears that the sea will one day swallow everything she calls home and her child will only know fear for the ocean and not the life and love she knows.

Another woman named Shawna Larson reflected on how her community in Alaska has some of the highest rates of cancer and illnesses due to DDT and other chemicals making their way into the sea and up into the Arctic, where it is in the fish they eat and then gets passed to children in the breast milk. She also commented on the power of storytelling and how it “makes you feel and feeling gives you responsibility and relationship to things.”

Indigenous communities not only understand the power of storytelling but they also have traditional knowledge. Traditional knowledge works to simplify the scientific jargon and numbers for communities. It attempts to bridge this communications barrier in order to allow more people the opportunity to be informed and to open a space for dialogue in order to have action.

Local people need to be involved and traditional knowledge is another tool that can work to bring their voices to the table.

One speaker from the Polynesian islands said how she used to contemplate if she was “good enough” to discuss and take on this climate change emergency. She said people of their islands always look to others for the answers, until they realized their own worth and traditional knowledge.

She remarked, “I’m talking as an expert about being a human in the Pacific, not as an expert about climate science.” But because she wasn’t a scientist it doesn’t mean her voice should be any less important. She wanted to humanize the Pacific and other indigenous communities and leverage them into positions of power, which needs to be done.