The following blog posts, written by student members of the UConn contingent to COP 23, emphasize the importance of solidarity and inclusion in the climate negotiations:

Redefinition: My Agency to Take Up Space Wawa Gatheru

Integrating Intersectional Feminism and Climate Policy Rebecca Kaufman

Women Revolutionizing the Environmental Movement Taylor Mayes

Warning! Climate Change is Real Colleen Dollard

UConn @COP23 Breakfast Clubs – Reconciling Science and Social Justice on Climate Change Jillianne Lyon

Redefinition: My Agency to Take Up Space

Wawa Gatheru, Environmental Studies, Minor in Environmental Economics and Policy

There is nothing more awkward than incorrect ideological association.

Over a year after the election of our most recent President and his infamous declarations of climate denial, perhaps the most frustrating outcome has been the ideological association placed upon the American people. As the United States operates under a democracy, the internationally perceived status of climate change legitimacy in the U.S. has mirrored that of our President – even while its alignment could not be further from the truth for most Americans.

I, along with 68% of Americans, believe in anthropogenic climate change. As a proud environmentalist with the hopes to dedicate her life to environmental justice, the ever-so accepted narrative of the American refusal to legitimize this fact has been frustrating. For so many, anthropogenic climate change is not just a distant fact, but a driver for action. And for me, the environment – its study, its appreciation, its protection – is my life.

So you can probably understand my distress at the thought that some of the most fundamental scientific truths about climate change might be overshadowed due to incorrect ideological association. And upon my arrival at COP23, this consciousness – one of possible incorrect alignment – discouraged me. How would I be accepted in the COP space as a dedicated environmental activist if my very nationality as an American could disqualify me from such a categorization? Could it also potentially disqualify my UConn cohorts and other U.S. citizens here in Bonn? Or worse – could this perception be another barrier for those who aspire to stand up against environmental injustices around the world?

Although these concerns raced through my mind during the weeks leading up to COP23, in the end, my interactions throughout this week at the U.N.’s Climate Summit in Bonn, Germany provided me with both a sense of relief and renewed inspiration. That’s because when I reflect, my cumulative experience at COP was more than just transformative. It was reaffirming.

Surrounded by hundreds of citizens, languages, and colors, I realized the following things:

I have the unalienable right to be a member of the climate justice movement. While my initial discouragement about my reception in the COP space was, and continues to be, legitimate, I must never, EVER question my right to take space in this movement. Every single relationship to the environment is valid and necessary in making long-lasting, sustainable, socially and scientifically competent change. Every single voice is necessary to accurately redefine environmental action as a non-partisan one.

There is no time for the exclusion of voices in this movement. During her presentation at the Women’s Earth & Climate Action Network conference, Noelene Nabulivou, founder of DIVA for Equality FIJI and one of the most incredible people I have ever had the pleasure to meet, said it best. “We are in a social revolution, an economic revolution, an ecological revolution – because we have to be.” Climate change and adequate solutions must be appreciated in relation to every sector – social, economic, and ecological – as this appreciation will lead to understanding the interconnections and level of accountability that must be taken. The #WeAreStillIn movement represented this shared accountability, as it included voices that are not usually heard in the environmental movement – namely those of the private sector. In continuing to make the climate justice space inclusive, it must also be said that while all voices must be heard to create the most riveting changes, certain voices must be at the forefront of this movement. Women, specifically women of color and indigenous women, MUST be at the forefront of this movement, as they are simultaneously the most adversely impacted by environmental degradation. In this fact, it is this demographic that should be valued as indispensable actors and leaders of just and effective solutions.

Finally, I realize that the takeaways I received from COP cannot and will not live in momentary appreciation. There is no time. Climate change cannot exist only as a subject for discussion, but as a topic for action. Because the devastation of climate change has already begun, and we must act. Together.

Integrating Intersectional Feminism and Climate Policy

Rebecca Kaufman, Political Science and Human Rights, Minor in Public Policy

“We need to reclaim the ideal of ‘the commons’ and reject the prioritization of technological and economic fixes.” This quote by Ruth Nyambura, an Eco-feminist and activist from Kenya, was one of the many that I have messily scrawled in my notebook from the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) event, ‘Women Leading Solutions on the Frontlines of Climate Change’ — a side event at the UN Climate Conference COP23. Throughout the course of this session I felt empowered, inspired, and angry. However, Nyambura’s sentiments capture the essence of what I took from the event.

When working towards climate change solutions, it is clear that we need to fundamentally change the way that we consume and interact with our environment. This is overwhelming and sometimes feels scary, if not impossible. Personally, I have always understood access to a clean and healthy environment as the fundamental human right upon which the realization of all other rights relies. What Nyambura gets at is the idea that if we are not spiritually connected to our environment, and by proxy the other actors that exist within it (both human and non-human) we will never be able to address the overwhelmingly complex issue of climate change.

The fact of the matter is that the people who are disproportionally impacted by climate change-related issues like flooding and drought (and the subsequent shortages of food, water and shelter) are not the primary ones contributing to antecedents of climate change, like over-consumption of animal products, food waste, and fossil fuel emissions, among others. Many of the most-impacted people include women, such as Nina Gualinga, the Kichwa leader from the Pueblo of Sarayaku, Ecuador, who is working to preserve the Amazon rainforest, and Thilmeeza Hussein, founder of the NGO Voice of Women and former resident of the Maldives.

As I listened to Gualinga and Hussain talk about defining ‘development’ in a way that empowers those in countries that are developing and the negligence of those pushing to continue the use of fossil fuels (including the United States’ heartily-protested COP23 presentation on “clean coal” – are you kidding me?) I became angrier and angrier that this incredible WECAN conference was merely a ‘side event.’ Meanwhile, those with the the highest clearance, those with the most policy-making power were sitting at the main COP venues listening to a panel of environmental injustice perpetrators, like Shell, discuss alternative energy.

When Gualinga asked the question, “who is defining development?” she is addressing the fact that voices like hers aren’t at the table with corporations like Shell. The people whose lives depend on the preservation of diverse ecosystems are not at the table. The people whose employers have caused and perpetuated climate change related disasters are.

There are a lot of reasons for this. I would argue that one of the most prominent ones is the fear among those in power that their power will be dismantled or changed in some fundamental way. Perhaps after decades of disenfranchising indigenous people in the Global South, these policy makers and corporations have had a moment of reflection — where they realized that what they did was wrong and that the process of making amends and distributing appropriate reparations will be painful and time consuming but necessary.

Essentially, I think that the persistence of unequal power dynamics stems from our lack of a spiritual connection to our environment and each other. And our inability to form this connection has the direct consequence of maintaining institutionalized inequality and a western capitalist culture of consumption.

It is problematic that corporations are so highly valued as change-makers, when by definition, the mission of a corporation is to increase their profits. Especially in America, where private corporations are not subject to the same level anti-discrimination rules as the public sector. Furthermore, while not all governments represent their constituents well, their chief role, unlike businesses, is to represent the best interests of their constituents.

Businesses (perhaps with the exception of B-Corps) hold a fiduciary responsibility to maximize the profits of their stakeholders, who often represent the world’s elite. This, to me, is completely inconsistent with the core values of social and environmental justice — to attain a sustainable network of systems that are healthy, equitable, and compassionate.

This is not to say that corporations cannot use their profitability to effect positive social and environmental change. We should just be skeptical of their willingness to do this effectively — especially when promises of corporate responsibility are proven to serve as effective marketing. Even in the panels I’ve attended discussing the virtues of corporate social responsibility, corporate leaders are incredibly transparent in discussing social and environmental impact as fiscally beneficial — rarely addressing the fact that we should just be kind to others. We just should.

80% of climate refugees are women and children. In Africa, although 80% of food is produced by women, 22 out of every 25 women live in poverty. During times of food and water shortage, which are expected to increase as climate change becomes more severe, women are more likely to go without food and die from starvation. So when female climate leaders like Hussain call out the negligence of industrialized countries as a “climate genocide by corporate greed,” why isn’t everyone there to listen?

“Women’s movements have always been in the business of territories — be it bodies, communities or the world,” said Noelene Nabulivou of DIVA for Equality and the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, Fiji. I will reiterate Nabulivou’s call to action because I think it is empowering and will inspire self-reflection. We are not all in this together. Climate change affects everyone, but people of color and women are impacted disproportionately. Failing to address climate change related disaster is a tool for maintaining institutionalized racism and sexism.

We need diverse bodies participating in climate negotiations. We need to mainstream the tenets of intersectional feminism into climate policy because intersectional feminism is inherently related to the power dynamics. A favorite quote of mine by Audre Lorde is, “It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.” It is the responsibility of our leaders to mainstream gender in climate policy. It is the responsibility of those in power to self-reflect on their bias. Negligence to do so perpetuates systematic sexism and racism.

Our identities are multifaceted and they intersect. And if there was anything that I took from WECAN’s event, it is that each of us has solutions. Those of us who have experienced institutionalized violence are often the most creative. And so, as stewards of the environments we occupy, it is our responsibility to use the privilege we do have to speak up.

Women Revolutionizing the Environmental Movement

Taylor Mayes, Environmental Studies and Political Science

On Monday, November 13th, UConn@COP23 attended an event at the conference called Women Leading Solutions on the Front Lines of Climate Change. The event was organized and hosted by WECAN, the Women’s Earth & Climate Action Network, International. WECAN is a climate justice-based initiative established to unite women worldwide as powerful in worldwide movement building for social and ecologic justice. The event took place at the beautifully eloquent, Hotel Königshof, located right on the Rhine River in the city of Bonn. The hotel had a very vintage-chic-feminine vibe which created the perfect back drop for the event.

Upon entering the space, one could truly feel the room radiating with warmth and life. Imagine a room filled with passionate women from a diverse array of countries, communities, cultures, and identities from all around the globe. It was so refreshing to be in a space filled with such richness and color.

Our group stayed for three of the events panels and keynote speakers; each panel consisting of talks done by a composition of four very wise and experienced environmental activists. This was well executed, as the purpose of the event was to unite women from all different walks of life to join in solidarity and speak out against environmental and social injustice as well as to draw attention to the root causes of the climate crisis.

Addressing the root causes of this crisis and having discussions about racial and gender injustices is a form of resistance, and it should be given a lot of credit, as it takes courage to be disruptive and to revolutionize the way we talk about the environment. This was especially true in the context of the mainly white male cisgender dominated 23rd Conference of Parties, where the “main events” were often very superficial and non-substantive.

Present in the very tone and essence of all of the talks was the idea that this issue of climate change and environmental degradation would not be solved until women, especially brown and black women, are given a seat at the forefront of decision making table.

I greatly appreciated the unique way this event united a group of women, who were all so different in so many ways, around a common cause. Women who had a diversity of experiences: coming from different places, celebrating different cultures and religions, speaking different languages, and in turn, who face different struggles. And yet, even though this theme of unity was present, it did not erase or diminish any of the women’s identities — but instead maintained that fine balance by celebrating those differences at the same time. There was spoken word, poetry, different languages being spoken (and translated), and even an indigenous women’s warrior song, all used to conveyed the experiences and witnesses these women had to the effects of climate change.

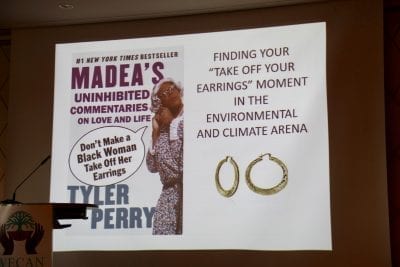

The event was so uplifting, and inspiring for many, if not all, of the women in the room. Our anger and frustration with current state of the world was not only validated, but re-inspired which does not happen often. A flame was lit underneath my passion and drive, and to use the words of our speakers, Katherine England, I felt my earrings literally fall off. This “side event” at COP23 was an experience that I will cherish for the rest of my life.

Warning! Climate Change is Real

Colleen Dollard, Geography and Maritime Studies

Warning! Climate change is real and affects millions of people around the globe every day. The longer nations wait to take action the more perilous these impacts are expected to become. More importantly, the people who have contributed the least to climate change will be the ones to face the brunt of it first. Drought, infectious diseases, hunger, and displacement are all disproportionately impacting women and people who are living in less developed countries.

Additionally there are islands in the Pacific that have already been lost due to the rising sea level. At the Women’s Earth & Climate Action Network conference, Thelmeeza Hussain from the Maldives reported that her home is subjected to saltwater intrusion. This has led to a loss of drinkable water, destruction of agricultural lands from sea salt, coral reefs dead and bleached white or in the process of dying, and an increasing frequency of dangerous king tides. These impacts are not a product of the actions of the people of the Maldives, yet they are unfairly affected by the fossil fuel businesses and consumption in developed countries, who continue bad practices despite knowledge of climate change.

Real change starts with opening up the floor to their voices, listening, then implementing the policies that were chosen by them for their communities.

Thank you, Fiji and Germany, for hosting COP23 and empowering voices that otherwise may have been lost in the conversation. I look forward to raising awareness back at the UConn Avery Point Campus and elsewhere about issues like the role of gender in climate change and the social injustices of loss and damage already incurred from its effects.

UConn @COP23 Breakfast Clubs – Reconciling Science and Social Justice on Climate Change

Jillianne Lyon, Human Rights and Political Science, Minor in French

One staple of our UConn@COP23 week was the ‘Breakfast Club,’ where the group gathered each morning for a faculty-led discussion about a climate change-related topic and to share thoughts about our experiences from COP-related events of the previous day. As a senior majoring in Human Rights, I have principally been exposed to social justice narratives and it was constructive to hear voices from students majoring in Chemistry, Engineering, Business, Environmental Sciences, Geography and Environmental Studies.

The students were at many times split between those studying humanities and those in STEM, challenging norms accepted in both fields. Should we be talking about racism when we talk about climate change? Should pragmatic science-driven solutions be given preference even if they discount or perpetuate discriminatory effects?

In my Human Rights classes, climate change conversation has always gone hand-in-hand with analysis of environmental injustices. My courses focus on issues like racialized housing policies in Flint, Michigan, or violations of indigenous rights like the Dakota Access Pipeline. Discussions are often people-centric and use rights-claiming language. Everyone has the right to clean water; everyone has the right to life, to an attainable standard of health, to nondiscrimination. However, this conception of climate change can be limiting and is often dismissed in countries where such norms do not hold much authority.

On the other hand, I have recognized that exclusively human rights-driven narratives are not sufficient for addressing existential environmental threats, like climate change, which demand immediate, radical action from the global community. It is infinitely easier to demand reduced CO2 emissions than it is to demand the destruction of the patriarchy.

Science-based targets and emission thresholds provide states and private actors with clear goals and limits that are accessible and attainable. Unfortunately, international environmental agreements, like the Paris Accord, hold no definitive binding power, and are only as effective as the ensuing commitments made and actions taken by each nation.

One thing that has been made very clear to me by my COP23 experience is that climate dialogues are often exclusive spaces. They are white spaces, they are Western spaces, and they are male spaces. There’s a push to highlight SIDS (Small Island Developing States), to include gender analysis, to incorporate social justice. But these efforts have brought us panels with token minorities and corporate leaders who are applauded for green-washed diversity programs. Climate dialogue needs to emphasize diverse and nondiscriminatory leadership if it wants to correct the issues that caused climate change in the first place.

The UConn@COP ‘Breakfast Club’ discussions raised many of these issues. Deliberating back and forth with a diverse group of UConn students about climate change priorities has reaffirmed my belief in multi-dimensional dialogue. Social justice and science driven solutions to climate change do not have to be and are not mutually exclusive. Science-driven policies can ignore systematic inequalities and exacerbate them in proposed solutions. Social justice claims can be disconnected from the capacity of governments and constraints in the private sector. The key is striking a balance between these two narratives without excluding or marginalizing voices that should be playing main roles.

Our daily ‘Breakfast Club’ discussions pushed me to think more broadly and creatively about climate solutions. For every UConn class talking about environmental discrimination, there is one talking about habitat evolution, and another talking about corporate social and environmental responsibility. My experience at COP23 has reassured me that it is vital to bridge this divide and engage in inclusive climate discussions. Without leadership from diverse narratives, both scientific and humanitarian, our planet won’t stand a chance against climate change.