Editor’s note: UConn@COP25 Fellows were asked to share their first impressions of their experience at the COP after the first two days of the conference. Here’s what they had to say:

42 Hours in Madrid – Louanne Cooley

Approaching Environmental Issues on an Individual Level – Sarah Schechter

The Impacts of Climate Change on Moana and Pacific Island Nations – Lauren Pawlowski

Thinking Beyond Borders & Labels – The Reality of Climate Migration – Megan Ferris

Commonalities across Cultures: Injustice for Identity Minorities – Xinyu Lin

Additionality a Must for Carbon Offsets – Hope Dymond

Human Emotions Influence Decision Making – Especially on Climate – Emma MacDonald

Technocrats vs. Radicals on Addressing Climate Change – Harry Zehner

The Climate Emergency Impacts Everyone, From the Queen of Spain to UConn Students – Matt Yang

Article 6 and Emissions Trading Systems – Alyssa Pagan

The Situation in mi Country – Danny Osorio

Technology is Critical to Helping Farmers Adapt to Climate Change – Himaja Nagireddy

Time for Action – Spencer Kinyon

Indigenous People at the Forefront – Michael Goccia

Who Do we Turn to when National Governments Fail to Lead? – Georgia Hernandez – Corrales

Questioning the Paradox of Sustainable Development – Mara Tu

Environmental Justice IS Social Justice – Natalie Roach

42 Hours in Madrid

Louanne Cooley – JD, School of Law

As I write this, it’s 1 AM and we’ve been in Spain for about 42 hours. Every minute here reveals greater depth and texture as I come to know more about this remarkable group of students, faculty and staff, all learning together about the complex issues around climate change, and all committed to expanding our role as citizens working for solutions.

Oisin Coghan- Friends of Earth Ireland

Lola Vallejo- IDDRI

Malta Hentschke- Klima Allinz

Yvon Slingenberg, EU DG-Climate Action (Photo: Louanne Cooley).

That we are here at all speaks to that commitment. UNFCC COP25 was originally to be hosted by Brazil, but with the election of a populist president a year ago, they withdrew. Chile stepped into the gap so the conference could still be held in South America, but the civil unrest in October of this year caused Chile to pull out too. With a month to go before the conference, Spain worked with Chile to provide a venue, and people worldwide scrambled to change travel plans to make it work. It’s a testament to how important these issues are that we are all here, eager to talk, listen, learn and take action, but many could not travel to Spain, and it is important to recognize that their voices won’t be heard this year.

The staff at UConn’s Office of Sustainability made a heroic effort to get us here, changing flights, finding new accommodations, making sure we would still have access. We arrived excited and grateful for the opportunity. After taking in the artistic treasures of Spain at the Prado and wandering the rainy streets of Madrid sampling tapas and churros yesterday, today was all business. We arrived at IFEMA Feria de Madrid early Monday having picked up our passes yesterday evening. The COP25 organizers have pulled off a real coup managing to move the venue from Chile to Madrid with a little over four weeks to completely revamp and reorganize. We jumped right in to attend side events, visit pavilions, and most importantly, meet people and learn about their ideas.

I’m a law student at UConn Law working at the Center for Energy & Environmental Law so I was eager to learn about legal frameworks for implementing climate action. The EU pavilion hosted a side event, Fighting Climate Change: The Legislative Response addressing a proposed EU Climate Change Law. Yvon Slingenberg, Director of International, Mainstreaming and Policy Coordination at the Directorate-General for Climate Action (DG CLIMA) in the European Commission, talked about a proposal to implement a system of tariffs on goods coming from countries that have failed to make their emission reduction targets under the Paris Agreement. That would be real change in policy to put a financial penalty on countries doing business in Europe to force climate accountability. I’m eager to learn more about the EU Climate Change Law and watch how it is debated and what provisions are enacted in the weeks to come.

In addition to the law surrounding climate change, I am also interested in how climate issues are communicated, especially to people without a science or technical background. One way to do this is through art. I’m a knitter and I’ve been involved with a global project originating in the US called the Tempestry Project. Conceived by Emily McNeil, Justin and Marissa Connelly of Anacortes, Washington, a Tempestry is created using climate data to make a visual representation of temperature change as fiber art. For the last month, I’ve been working on a “Global New Normal” Tempestry using annual deviation from average temperature from 1880 to the present and inspired by Dr. Ed Hawkin’s warming stripes climate visualization work. Working on the project is a way to engage with the process of temperature rise which isn’t really perceptible on a day to day basis. Watching the years of progress as I knit, the darker blues dropping out to be replaced by lighter colors, then darker and darker reds, it is impossible to ignore how our planet has changed. I had a chance to talk to Rahul Bansal of the United Nations Climate Change Secretariat at the UNFCCC Pavilion about the project and showed him my work. Seeing and touching the Tempestry is a very powerful way to connect with what can be an abstract process. Rahul was so taken with the project that he thought the UN might be interested in displaying Tempestry next year at COP26 in Glasgow. Being able to connect to people is one of the huge benefits of being here at COP25. Many of the speakers I heard today made the point over and over that climate change is about people. Solutions need to be people focused and need to reach everyone. Everyone has a role to play, whether as a scientist, policy maker, educator or citizen in accepting responsibility and working for change.

It’s now Tuesday and after a few brief hours of rest, we are back at COP25. Today there are more pavilions to visit, events to attend, and people to talk to. So many people to talk to with ideas and hopes and fears, willing to listen to each other and work together. That really is the most hopeful part of being here, surrounded by people, all in it together. It is time for action!

Louanne Cooley is a third-year student at the University of Connecticut School of Law. She is a research assistant at the Center for Energy and Environmental Law at UConn Law and is pursuing a Certificate in Energy and Environmental Law. Follow Louanne on Twitter @louanne_cooley and on Instagram @louanne.at.cop25

Approaching Environmental Issues on an Individual Level

Sarah Schechter – BA Environmental Studies and Anthropology

We constantly hear the phrase “think globally, act locally,” but how do we actually put that into practice? When we act on a local level we are trying to benefit the town or municipality that we are working with, but what if that’s still too large of a scope?

Walking into Day 1 of COP25 I was unsure of what to expect, in awe of the bright lights and intricate booths. One was made from cardboard, another had a wall of plants, and still another had a giant Earth sitting in a dish of ice.

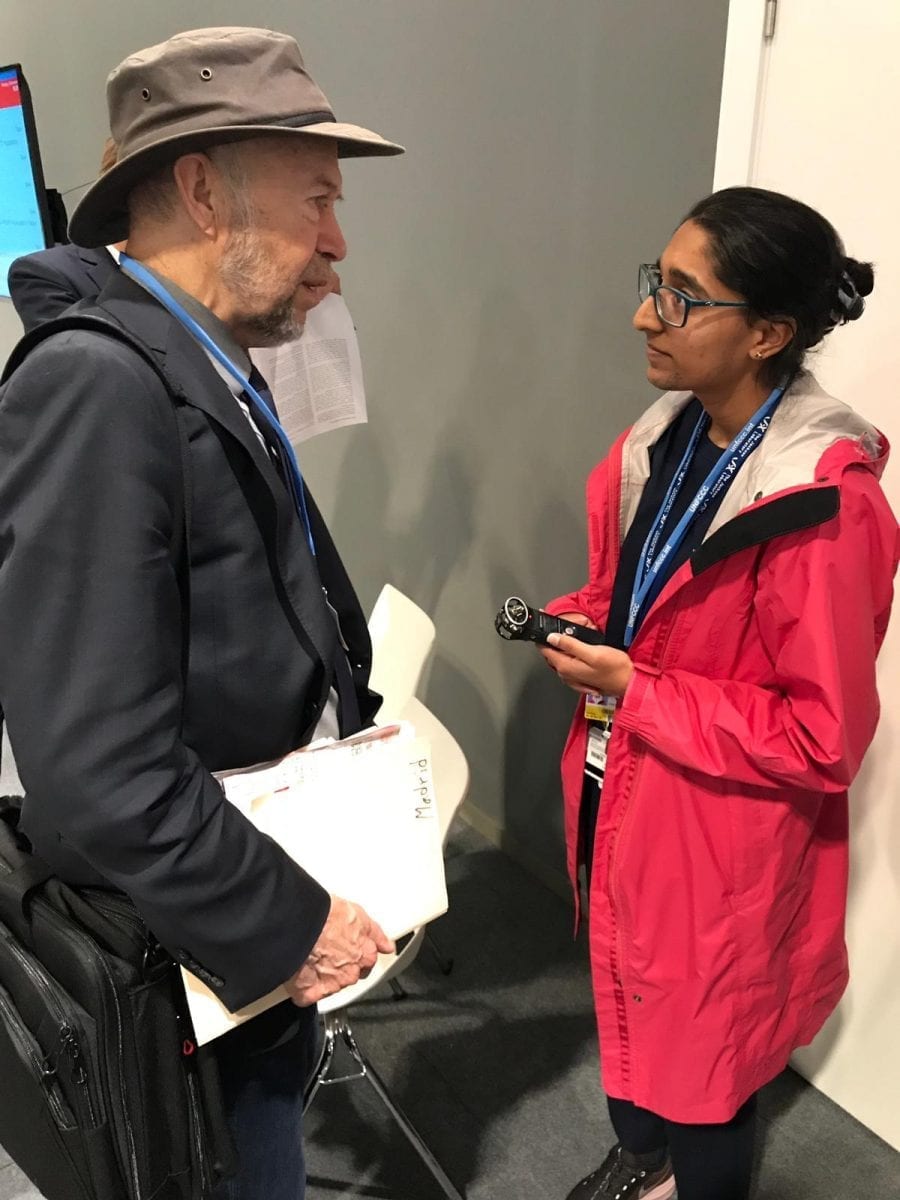

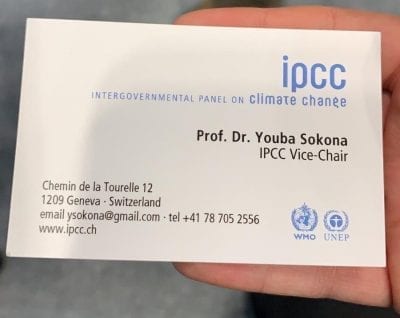

I made my way to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) booth, prepared to discuss volunteering with them later in the week. I was then introduced to the Vice-Chair of the IPCC, Dr. Youba Sokona, who asked the group “What are you doing on an individual level?” We started to answer with what was being done in our communities, but he adamantly asked again, “But what are you doing?”

I chimed in with what I try to do on a regular basis and he seemed satisfied. However, this spurred my mind in the direction of how we go about solving daunting environmental issues. Perhaps we aren’t breaking them down enough, clouded by the anxiety of the terrifying concepts.

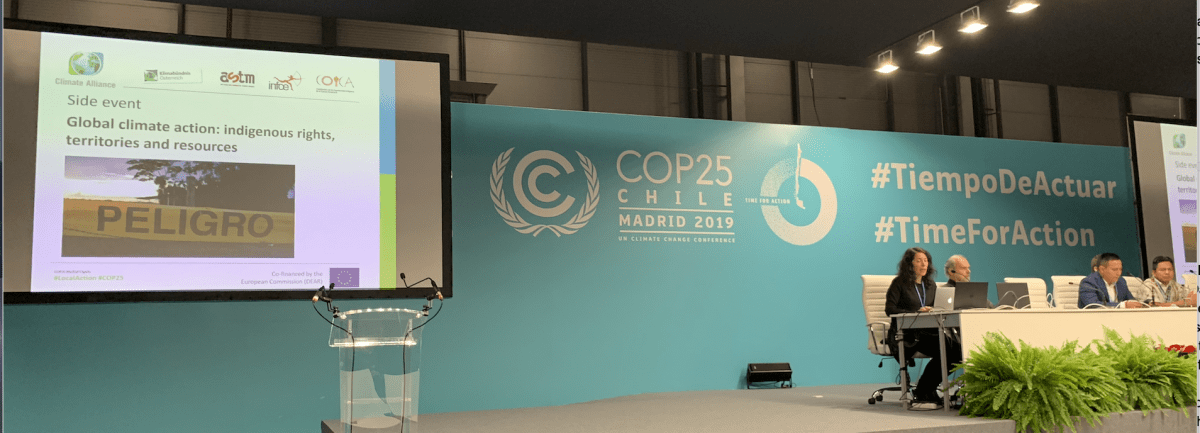

Later I attended a side event titled, “Global climate action: Indigenous rights, territories and resources” in which the Director of Energy 2050 posed a similar question. He looked at the room full of international individuals, all with diverse backgrounds spurred by different interests, and he asked, “What are you doing?” He followed this with encouragement to go out and educate the world, echoing with the idea to “Do your part.”

There it was again, a reminder for individual action and that everyone’s contribution matters when combating climate change.

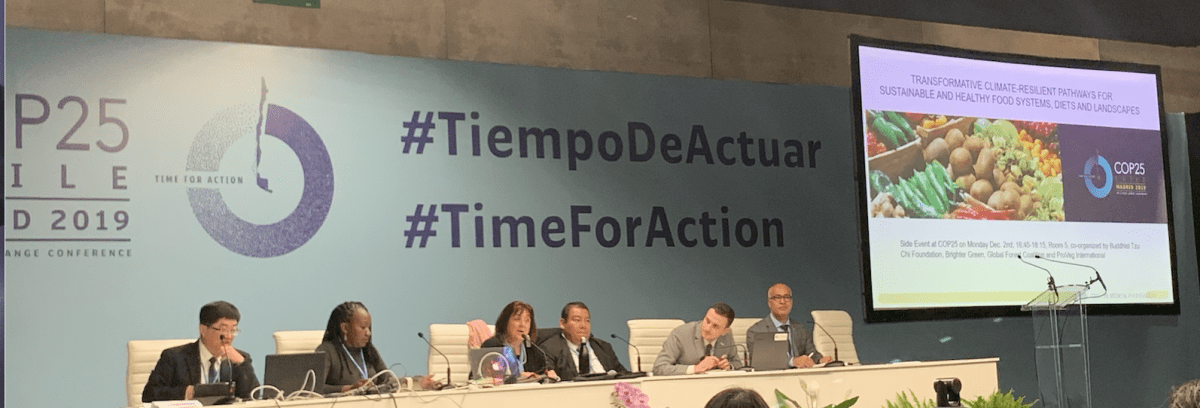

Another side event, “Transformative Climate Resilient Pathways for Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems, Diets, and Landscapes” focused on the production and consumption of food around the world. Plant-based diets were heavily discussed by the panelists, who supported the act of becoming vegan or vegetarian for health and environmental purposes. Deputy Director of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), Zitouni Ould-Dada, said that the responsibility is on the people. He made it clear that he was not there to force anyone to switch to a plant based diet, but he reminded the room that each person decides what they choose to eat. While there was some controversy regarding this statement, due to socioeconomic factors that can take away choices, he still brought up the idea of individual action.

In one day, I heard about approaching environmental issues on an individual level three times. Clearly, there is the desire to break down problems surrounding climate change into more manageable tasks. While I personally think that acting on a larger scale is still valid and important, because it allows for a broader response, I do see why individual action must still be present in the conversation. I look forward to the rest of my time at COP25 and I wonder when the call for individual action will be mentioned again.

Sarah Schechter is a junior from Danbury, CT, double majoring in Environmental Studies and Anthropology.

The Impacts of Climate Change on Moana and Pacific Island Nations

Lauren Pawlowski – BA Environmental Studies and BS Economics

In the first hour I spent at COP25, I felt lost. This is my first time at a conference this huge and important; I didn’t want to miss out on any chance to listen to world leaders, talk to representatives of international organizations, and see all of the exhibits. There were so many events happening all at once — I couldn’t decide where to head first. However, I quickly figured out where to go to see each country’s exhibit space or “pavilion” and where to listen to panel speakers at the side events.

Part of the magic of COP is finding out about little happenings from talking to different people you meet. Towards the end of the day, a group of the UConn@COP25 Fellows and I were tired, hungry, and mentally drained, but we met a funny man from the Himalayas who convinced us to stay longer.

He told us about his work in planting millions of mangrove trees in the Pacific Islands region and why this was so important to restoring coastal ecosystems and maintaining indigenous communities. His passion for the oceans drew us to stay and participate in the ceremonial welcome event at the Moana Blue Pacific Pavilion, which was happening in 10 minutes. It started out with the island natives performing songs and saying blessings in their indigenous languages. They also taught us traditional greetings in these languages as well. I quickly learned that the term “moana” is used to describe the sea or the ocean and that these island communities from countries like Fiji, New Zealand, and Tuvalu are very proud to be presenting a unified front focused on the importance of oceans at COP25.

In a collective communal prayer, they were thankful for having representation from the island countries, for being in a space to talk and share experiences, and for the opportunity to connect with as many people as they could at this event. It surprised me how welcoming they were to all, even though their island nations and tribal communities are facing the worst effects of climate change, including sea level rise and collapse of coastal ecosystems. They were insistent on having everyone try the kava drink, which is a tea-like beverage often used for medicinal purposes in Fiji, and on taking a group photo with flowers in our hair.

While this welcoming ceremony was peaceful and sweet, the UConn Fellows and I learned more about the issues the islands face when talking to the delegate from Fiji. He told us how frustrated his community was with the conversations at COP; he believed they were too focused on emissions reductions and energy. He told us that his goal for this conference was to add the topic of oceans to the mix, because he said that without protecting aquatic animals, plants, and the coastal ecosystems, indigenous communities could lose their livelihoods. Everyone around the world relies on the ocean for fish, other food products, recreation, and ecosystem services. He said even if we prevent emissions we must also prevent ocean pollution and degradation. Without this, the world will face legal challenges to deal with climate migration of island communities. One of the closing remarks at the ceremony was from the Fiji representative, who spoke about how we are all in a collective canoe, which “takes the message of our people, of our life, of our ancestors” and how we must join in this canoe together and share experiences to tackle the climate issues along this journey.

We cannot forget the voices of indigenous communities and the sinking islands around the world. We must not only prevent climate change, but also protect existing aquatic and coastal ecosystems for a socially and environmentally sustainable future.

Lauren Pawlowski is a sophomore from Shelton, CT. She is pursuing a BA in Environmental Studies and a BS in Economics as part of the UConn Honors Program. Follow her on Twitter for the latest COP25 updates @laurepawlowski

Thinking Beyond Borders & Labels – The Reality of Climate Migration

Megan Ferris – BS Environmental Science

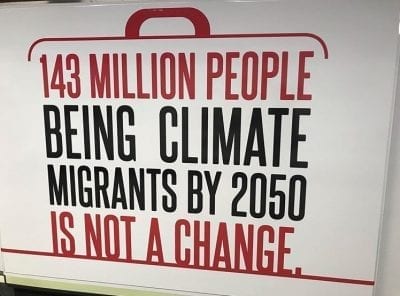

What I was most excited about seeing at COP was the involvement and discussions of climate migrants. During previous years at the COP, the term “climate migrant” wasn’t mentioned quite as much as it already has been in several of the opening panel discussions at COP25. The concept of environmental migration — a very politically — and socioeconomically-charged issue has been swept under the rug. But as our seas rise, more people from island nations and coastal communities are being forced to move inland or to mainland countries to look for new homes -two examples of this displacement are the Carteret Islanders and the people of Bangladesh.

After just the first day at COP, and with a hopeful mindset, I attended two side events revolving around issues of environmental migration. At one of the events, the speakers brought up a new potential solution called the Nansen Climate passport, which would secure migrants’ access to Germany and remarked, “at least the kinks start the discussion.” This acknowledges the importance of beginning the conversation about new solutions and getting past the hurdle of inaction, despite the challenges and issues that will inevitably occur.

Another aspect of this issue I found interesting was the notion of clear and unambiguous terminology. Referring to “climate-induced migrants” directly assigns responsibility and raises awareness about the consequences of climate change, especially as they affect populations that have had so little to do with causation. I find that accepting responsibility is something many countries fail to do.

With this in mind, it would help to observe the inter-sectional realities of a country’s citizens, including environmental migrants, who were forced to leave their homeland, and shouldn’t be penalized or criminalized for doing so.

The panel brought up a point that I appreciated, which was to “think beyond borders, beyond labels, and as a global community.” No one wants to leave their own home, and as the number of climate-induced migrants increases each year, we need to start raising awareness and motivating more solutions to this complex interdisciplinary issue. We need to make sure that climate-induced migrants of the world are protected. As I continue my experience at COP25, I hope to see more discussion and solutions proposed!

Megan Ferris is a senior from Danbury, CT and class of 2020 Environmental Science Major/ Animal Science Minor

Commonalities Across Cultures: Injustice for Identity Minorities

Xinyu Lin – BS Civil Engineering

The American environmental movement is not secretive about its lack of diversity in leadership. Despite recent pushes to increase representation for identity minorities in decision-making positions, the gender and racial gap is undeniable. Women of color are left unheard while suffering the heaviest effects from the climate crisis.

As my third day at COP25 ends, I’m left reflecting on how diversity & representation issues appear across different cultures. It might seem obvious that there are marginalized groups in every country, but I’m well-aware that my understanding of equitable participation is heavily rooted in the uniquely diverse makeup of America. These past few days at COP have provided me with a privileged opportunity to interact with people in other countries experiencing climate injustice first-handedly, and to thoughtfully process these ideas in conversations with other UConn@COP Fellows.

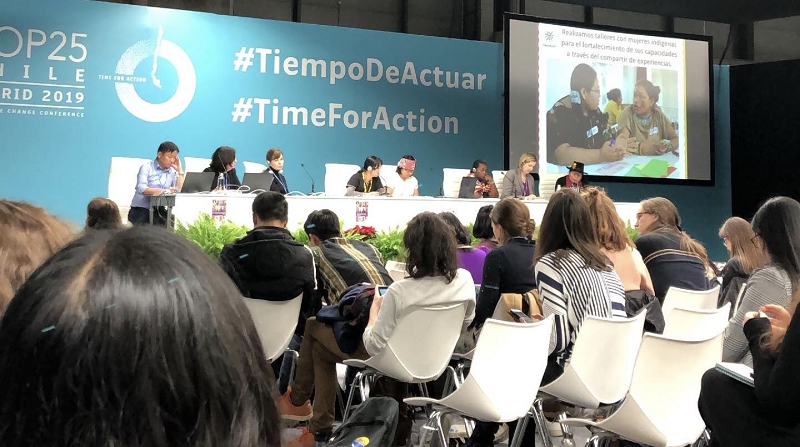

A side event I attended titled “Indigenous Women: Frontline Defenders in the Fight Against Climate Change,” featured women with origins ranging from Tanzania to Myanmar sharing their experiences as leaders at the front lines of the climate emergency. Even in these countries with racial homogeneity and defining cultural identity, indigenous women are the pillars of community and hold sacred knowledge on medicinal practices, ecology, and food production. As Pirawan Wongnithisathaporn of the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact said, “we are the ones who protect the land, and who have been doing it for a long time.” Her voice is a reminder of the knowledgeable female leaders who are well-informed on the problems and solutions facing their own peoples.

A powerful theme amongst identity minorities is amplifying across national boundaries. Despite the Global North’s attempts to propose market-based solutions and technological fixes to the climate emergency, efforts must be concentrated towards funding projects at the community level. We need our decision-makers to reflect the people being most directly affected.

Xinyu Lin is a senior studying Civil Engineering with minors in Environmental Engineering and Math.

Additionality a Must for Carbon Offsets

Hope Dymond – BS Environmental Engineering, Minor Human Rights

I assumed I would know most of the buzzwords here at the Conference of the Parties. For example, you will hear about the Paris Agreement, signed in 2016 as a treaty among many of the world’s countries. In the agreement they committed to reducing emissions, adapting to climate change and financing these shifts. NDC’s, another important term, are Nationally Determined Contributions, made by each country to define the amount it will “contribute” to the global effort to reduce emissions; a country by country target required by the Paris Agreement.

However, if you walk around this year’s COP 25, or even look it up online, you will hear about a new topic: Article 6. Don’t know what that is? Neither did I the first day I arrived at the conference! But now I understand it is of vast importance to the negotiations taking place here.

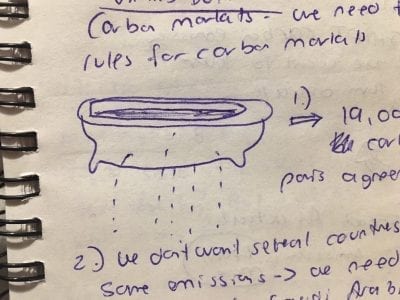

It was Monday morning, our first event, hosted in one of the spacious press conference rooms. A small group of us UConn students sat in a row among many white plastic seats, and listened as the moderator asked questions on general topics. Evocative speakers they were, but generic.

The third person to speak was a slender French man with glasses. I sat down with my tiny notebook open, and just like I had done for the other two speakers, I wrote down his name and started jotting in bullets of what he was saying. Soon this name, Guilles Dufrasne, was surrounded by stars denoting real importance.

What was he saying? That we need to “finalize the rules for carbon markets.” Ok, cool. He continued, “There are 19,000,000,000 carbon credits crushing the Paris Agreement from the inside.” Dramatic! I was intrigued. “Article 6 is where this will be discussed.” Now I had to learn more about this Article 6, whatever it was. Turns out it is part of the Paris Agreement, a part they are working on finalizing this year at COP in negotiation halls.

A visualization came next. Guilles said picture a huge bathtub, one with many little holes in it. The point of carbon markets here is simple. Emissions of greenhouse gasses that warm the planet are assigned a price per unit. If I am a country, say Spain, and I want to reach my Nationally Determined Contribution target, I can lower my own emissions. But that might not get me all the way there, and I still emit. So I can “buy” carbon credits from another country, say Costa Rica, which is basically me investing in a carbon reduction project there. There are many examples of projects that take greenhouse gasses out of the air, and the result of these market efforts should be an eventual lowering of overall carbon emissions. Back to the bathtub. Carbon pricing has been tried many times before, and failed many times before. All of the little holes in the tub are places where the policy is “leaky”.

One hole in the tub is extra carbon credits from previous projects. If there are trillions of them they will flood the market and crash the prices. Countries will just use these “credits” from the past to trade, and no real reductions project will take place. I am no economist, but this made dire sense to me.

One hole in the tub is lack of additionality — where projects that can be invested in for carbon credits are not sucking in any more carbon from the air than they would have in the first place. Forestry projects are a good example of this. Pretend I am Spain again. I buy some carbon credits from my pal Costa Rica, paying them to protect 1000 acres of trees to offset a certain amount of CO2. We all know trees are good for that! But the trees were already going to be protected. We had no plans of cutting them down! In fact, my carbon offset has created no additional reduction in atmospheric carbon, while I am polluting to add additional carbon into the air.

These failures in policy are grave. One tiny hole in the tub and all the water — every drop — will come flowing out.

If carbon markets are done incorrectly they will add carbon to the air in vast quantities; according to a World Resources Institute report the amount of carbon added through faulty implementation of Article 6 could be more than all the reductions proposed by every country’s NDC combined! Before this policy could even begin to be implemented on a worldwide scale, it has to be airtight. No leaks.

This is not an easy thing to do. In reality, it is a momentous task, and there is a diversity of opinion on every aspect of carbon pricing. In my subsequent days at COP the knowledge and controversy on Article 6 just kept coming in. Some people I listened to at COP say it is all pointless, some say it will always have negative consequences. I have talked to other experts that insist it can be done to great benefit, and understand the intricacies of involving human rights into the conversation. These are all topics for my next blog post. I hope I have left you more informed and a little more intrigued.

Hope is studying Environmental Engineering with a minor in Human Rights.

Human Emotions Influence Decision Making – Especially on Climate

Emma MacDonald – BS Natural Resources

The physical setup of the United Nations Conference of Parties (COP) is a product of the values of western society as a whole.

The venue has separate outdoor entrances to the green and blue zones on opposite sides of the building. The green zone is just one of the six rooms, while the blue zone is five rooms. As may be predicted based on this info, the green zone is meant for the general public, and is more colorful and fun, while the blue zone is only admissible with a pass, and is where all of the negotiations and official side events occur.

This is a concrete example of shoving the more jovial side of our humanity aside in the interest of remaining logical and unemotional in our policy decisions, which I believe to be a mistake. The general public may be argued to pose a threat to the event and proceedings of the COP, but there should be an integrated method of interaction between the general public and the delegates/countries in the blue zone. Instead, the two parties are separated by walls and security checks.

The Moana Blue Pacific Pavillion (located in the blue zone in room six) did a wonderful job of combining business with celebration in their opening ceremony on Monday evening. They opened and closed the event with music and food, and spoke about their hopes to bring discussion of the oceans to the negotiation room soon.

Important decisions should be based in logic and facts, but it would be remiss to exclude emotion, especially positive, joyful emotion, from the decision making process. If humans didn’t experience love and happiness then we would have no passion or motivation to continue.

It is true that the current definition of professionalism has an important place in the order of the world and especially in the topic of climate action. But it is also necessary to bring fun and lighthearted joy into professional spaces so that the ones making the “big” decisions are reminded of why they care in the first place.

How can leaders be expected to make good, holistic decisions if they are weighted down by fear of what we may become and grief for a world that could have been- rather than lifted by the gifts the world is giving us?

Emma MacDonald is a junior in the College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources. She is a Natural Resources major with a focus in sustainable forest management. You can follow Emma on Instagram @emmacdonald8

Technocrats vs. Radicals on Addressing Climate Change

Harry Zehner – BA Political Science

COP25 is a tale of two worlds. Although all observers, parties, and press are gathered here to find a solution to climate change, there are two distinct groups which view the problem through dramatically different lenses. On the one hand, there are what I will call “the technocrats.” This group earnestly cares about climate change. They believe in the power of markets driving innovative technological solutions and carbon tax schemes. When you go to the panels populated by the technocrats, you get a sense that they believe climate change is a policy problem. They believe that with the right regulations, market incentives and private investment, catastrophic warming can be averted. They pay lip service to the social problems exacerbated by climate change— such as gender, racial, economic and immigrant injustice — but rarely seek to challenge the systemic issues at the root of these injustices. Fundamentally, they believe that our system can be tweaked to beat climate change.

I’ll call the second group “the radicals.” This group is generally composed of indigenous activists, global south NGOs, and representatives from least developed countries. They also care deeply about climate change, but more importantly, they care about climate justice. While their panels do discuss substantive solutions, they generally cast a broader net than the technocrats. They tie climate change back to colonialism and our extractive economic system. The radicals understand that all issues are deeply connected to climate change, from indigenous land rights to migration. Rather than constraining themselves to technological solutions, the radicals envision a world built on community and regenerative life rather than exploitation and profit. They envision a post-climate change world that is better than our current iteration, one that is truly democratic and just.

In the official negotiations, the technocrats from developed countries almost always win. They have the economic clout to sway negotiations and disregard poor countries’ priorities. But in the halls of COP25, the radicals offer a crucial ideological counterweight. Their passion and systemic analysis is necessary to understand the scope of the problem and work towards a just future for all of humanity, not just the privileged few.

Harry Zehner is a Junior political science major with a minor in environmental policy and economics.

The Climate Emergency Impacts Everyone, From the Queen of Spain to UConn Students

Matt Yang – BS Civil Engineering

There are a lot of expectations when you hear the name United Nations Climate Conference. Some of the greatest scientists, activists, and most powerful political figures in the world converge to this one conference center for two weeks in order to negotiate and address the most pressing issue of our generation. Yet here I am, a lowly college student from Connecticut, somehow standing 15 feet away from the Queen of Spain. Yes, that really did happen.

As you enter the venue at Feria de Madrid, you are greeted by the sheer metaphorical and physical scale of the event you are attending. Walking into the first conference room is what I would imagine walking into an aircraft hangar would feel like. That was just the first room as well, there were five more identical rooms that beckoned for exploration. Needless to say, it was a bit overwhelming. With a conference that has more than 20,000 delegates from nearly 200 nations, I found myself constantly eavesdropping to see if I knew what language they were speaking or what country they were from. I came to a quick realization that I’m not as good at geography as I thought I was.

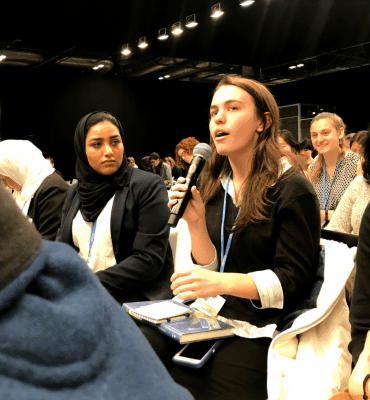

The first day I felt my heart pumping out of my chest, and my anxiety building up as I made my way over to the first COP panels of the day with some of the other UConn@COP25 members. The highlight of the day was attending a panel named Transportation & Oil: Phasing out Diesel Engines and the Fuel They Use to Meet Paris Agreement Goals.

There I posed a question to one of the panelists about the role autonomous vehicles will play in meeting these goals. This sparked a heated debate with other UConn@COP25 members. Despite having differing opinions and methodologies, it was a nice realization that we were all striving to achieve the same goal of decarbonizing our transportation system. It’s an extreme privilege to have peers who have differing opinions, whom you can collaborate with and engage in a respectful debate. These types of conversations have easily been some of the highlights of the trip so far.

The second day I sat in on a panel discussing how big data can be used to create meaningful climate solutions. This panel discussed how data is currently being used by companies like Qlik and Deloitte to quantify and create carbon report cards. With these report cards, they are able to collaborate with C40 cities, which is a group of 94 cities across the world focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This was a refreshing change of pace, since many of the panels I sat on before were focused on policy based solutions, however this panel aligned with my passion of using technology for social good.

The message of this COP has been that this is no longer climate change, this is a climate emergency. We must act quickly, and that’s why finding ways to use technology such as big data and artificial intelligence to create meaningful climate solutions is extremely important. While policy based solutions are incredibly effective, technology is much quicker to build and scale. Both however, must be used in conjunction if we ever want to build a sustainable society.

Matthew Yang is a senior, majoring in civil engineering.

Article 6 and Emissions Trading Systems

Alyssa Pagan – BA Political Science & BA Art

Article 6

One of the major topics of the United Nations Climate Change Conference has been Article 6 of the Paris Accords. This article has been an issue in the negotiations since its conception in 2015 at the UN Conference of Parties (COP) 21. It is still a disputed article and has yet to be fleshed out and agreed upon between parties. The article would enable countries to trade carbon emission permits between each other in an emissions trading system.

What are Emission Trading Systems?

An emissions trading system would enable countries to cooperate on reducing their emissions. Countries have set their own limits for pollution. These limits are goals set by the countries for their reduction of emissions. These limits are referred to as Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs. If a country develops more efficient or renewable energy and technology, they will reduce their levels of emissions as long as the growth in consumption does not exceed that reduction. If they are below their target they may sell, or trade, their emissions to other countries.

Article 6 has been under debate for so long as it has been difficult for the negotiators to agree on the rules. Many countries fear the issue of double counting, which is when the seller of a carbon trade and the receiver both count the reduction as their own. This would help more countries reach carbon goals but would negate the entire reason for the emission trading system — to reduce overall emissions.

Concerns with the Negotiations

At a side event titled “The Right to Climate Justice: Collective Convergence for Just Solutions and Against Geoengineering and Other False Solutions,” leaders involved in climate change efforts from El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Nigeria, and the United States, warned how geo-technology and carbon trading markets will not work to meet the 1.5°C goal established at the United Nations COP21. One of the major concerns brought up at the panel was that carbon trading and geo-technology only treat symptoms and consequences of climate change, they do not tackle the root of the problem, consumption.

Another major issue with Article 6 was its lack of differentiation between the industrialized countries, many of whom have historically contributed the most to the current carbon dioxide levels, and the developing countries. Unlike the carbon market article of the Kyoto Protocol, where developed countries such as Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark amongst others, referred to as Annex II countries, bore much more of the financial responsibility for climate measures, article 6 of the Paris Agreement enables all countries to be part of the emissions trading scheme. It can be argued there is some inequity in the target setting, as many of these developed countries did not meet their initial goals in the first stage of the Paris Agreement. Now, that emissions gap grows and has been effectively pushed onto the developing countries.

NNimmo Bassey, a representative from the NGO Environmental Rights Action in Nigeria, posed the question, “What are we doing here pretending to talk about solutions?”

He then went on to describe how we know what to do, we must cut our consumption and leave fossil fuels in the earth, not open up an opportunity for companies and countries to continue to pollute. His speech stressed the urgency of climate change. Many countries are already bearing the burden of climate change while some of the biggest polluters continue to not take action, or worse, deny it is even a problem.

So far, I have found that panel to be the most impactful to how I have been thinking about the issues of climate change. The radical need to transform the system and not stick to the status quo of exploiting the Earth’s natural resources highlighted that low set targets and non-stringent rules on the emissions trading system pose a real threat to the 1.5°C goal of the Paris Agreement. Overall, I felt that the negotiations needed the sense of urgency of this panel.

The Situation in mi Country

Danny Osorio – BS Molecular and Cellular Biology and Marine Sciences

I spent most of my morning talking and listening to the delegation sent from Colombia to the United Nations Conference of Parties (COP).

It was sad. It is true that there are a number of projects lead by both non-governmental organizations and the public sector of Colombia.

Colombia is prepared to fight climate change but at what price?

Most of the sponsors are investors that want to do bird watching in our region at the expense of social development of small communities, or worse, the suppression of environmental leaders from indigenous communities because their solutions do not align with the western vision of conservation.

But the delegation at the Columbia pavilion said Colombia was fighting climate change. They said that it is true, deforestation in Caquetá is slowing down, however, I know the Amazon has been experienced an exponential increase in deforestation in the last year alone.

When I asked for an interview, the delegation told me that they couldn’t give one. They told me that they didn’t have a political position in the situation our country is experiencing.

It was as if the lives lost in protests in the streets of Colombia where just a political opinion. As if hundreds of indigenous leaders weren’t murdered since 2016, over 100 in less than a year alone.

They were censored by the government, there wasn’t any other explanation. Their families were suffering but they didn’t have an opinion, not possible.

It leaves me feeling uneasy in thinking that the Colombian government doesn’t have the backbone to fight for the rights of its people on international grounds and much less to hear the voice of our nation that is agonizing in the streets.

Something was solidified for me today, ”los tibios se irán al infierno” — people that don’t support their country and don’t have an opinion in a situation like this are ‘condemned’, and they should be participating in the negotiations.

Danny Alejandro Osorio was born in Colombia and is a junior studying Molecular and Cellular Biology and Marine Sciences.

Technology is Critical to Helping Farmers Adapt to Climate Change

Himaja Nagireddy – BS Molecular and Cell Biology, Physiology and Neurobiology, and Sociology

As the child of immigrant parents who were born and raised in farming families, I have come to appreciate the importance of promoting farmer resiliency as a way to support food security. Innovation in the agriculture and food sectors is a growing field that promises to do this, which would address poverty in many rural farmer and consumer communities around the world.

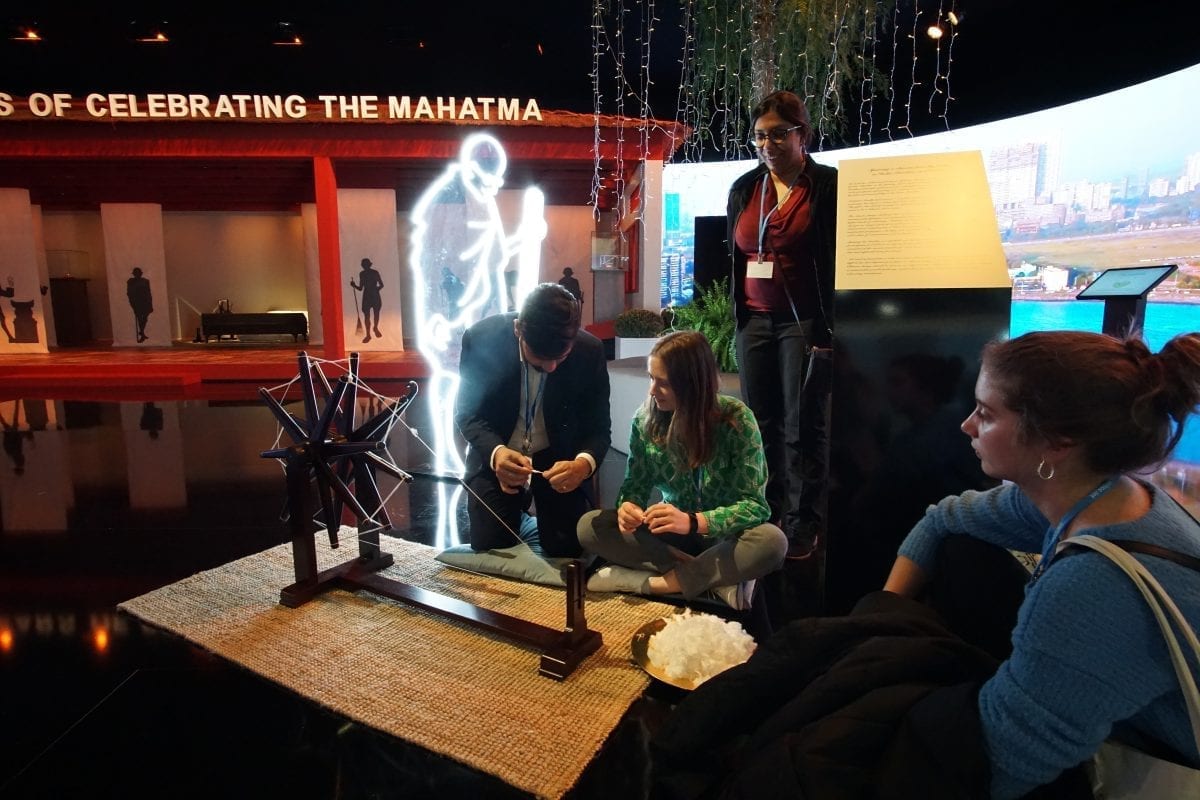

This topic, as well as other climate mitigation and adaptation innovation topics, were discussed at the Side Event on Science and Innovation in Support of Climate Action for the Poor and the Vulnerable. The panel consisted of various NGOs, government, and UN representatives who specifically addressed the importance of science and innovation to support a human rights-based approach to climate action and to promote climate responsiveness and social protection.

During the event, panelists discussed current projects to develop seasonal forecast models to inform farmers about ideal crops to grow and what weather conditions to prepare for that can damage crops. In addition, such a model would allow farmers to estimate their annual crop yield, which is data that can be used to address issues of food security. In order for the model to be to be scalable, data from different regions needs to be centralized and the data needs to be able to predict for multiple weather scenarios.

I think it will be interesting to see how such machine-learning models can be applied to better inform agricultural practices and improve crop yield, which would be beneficial to both farmers and consumers. Such innovations, as mentioned in the panel, have to demonstrate a measurable impact in promoting farmer resiliency and adaptability as a method of promoting food security.

In addition, these technology efforts need to bring together researchers, policy makers, and community members, specifically farmers. By facilitating dialogue between these different stakeholders, the technology that is developed can better cater toward the population it is trying to serve. This also bridges the gap between the “last mile” to ensure that such solutions are actually being implemented and have a significant direct effect for farmers.

Innovation in the agriculture and food sectors is critical to ensuring that initiatives can have strong impacts on climate change, poverty, and human rights. It will be interesting to see how other events at the 25th United Nations Climate Change Conference of Parties (COP25) address the need for innovation and technology and discuss the multifaceted benefits of such approaches.

Himaja Nagireddy, from Acton, MA, is a senior undergraduate student pursuing three degrees in Molecular and Cell Biology, Physiology and Neurobiology, and Sociology with a minor in Chemistry.

Time for Action

Spencer Kinyon – BS Political Science and Economics

The central message of COP25 is #TimeForAction, which has been embedded in all discussions and on nearly every poster throughout Madrid. On the first day of the conference, Dr. Youba Sokona, the Vice-Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change asked myself and fellow UConn students, “What is an individual action that you have taken?” He was not curious about whether or not we recycle, use LED lights, or have a car with good gas mileage. He was really asking about the efforts we have made to transform our communities for the better.

The question has stuck with me over the past couple days. In America, we believe that simple changes in what we do with our waste, choices about light bulbs, and the gas mileage on our cars are enough to reduce emissions. The question made me realize that our political conversations and debates regarding climate change are centralized on pushing others to change their behavior. However, few of us are willing to substantially change our own behavior.

The most inspirational speaker I have heard from was Ambassador Ronald Jumeau from Seychelles. In his speech, Ambassador Jumeau spoke of the impactful actions that Seychelles, which is an island ocean state, has taken to combat climate change. The efforts of island ocean states have included expanding sea grass areas, mangrove forests, and wetlands in order to mitigate the effects of climate change and prevent their nation from disappearing. Ambassador Jumeau stated the important point that island ocean states produce less than one percent of carbon emissions in the world, but have become responsible for trapping the carbon of the rest of the world and fighting climate change.

These nations have structured their economies and environmental policies, while having to pursue policies that do not give people jobs or ensure economic development in order to stop climate change. I found this extraordinary because these countries are not pursuing incremental actions, but are taking powerful actions. At COP25, I have realized that Americans truly need to step up their own individual decisions to be able to live in a more sustainable world. I am beginning to think more about the ways Americans can take actions in our lives that can improve sustainability and reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. It is time for Americans to take bold action on climate change.

Spencer is a Senior pursuing a degree in Political Science and Economics.

Indigenous People at the Forefront

Michael Goccia – BS Management and Economics

My first day at the United Nations Climate Summit & Conference of the Parties in Madrid, Spain was very exciting. After our morning “breakfast club” group discussion and metro ride to the venue, we set out to explore everything COP25 had to offer. I was fortunate to meet the Vice Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) who highlighted the importance of individual action. I was also able to participate in several panel discussions on a variety of topics ranging from the adaptation of technology to mitigate the impacts of climate change to a discussion on the rights and resources of indigenous groups. These discussions were very informative and impactful, with a wide range of perspectives and ideas being expressed.

It was eye opening to hear from Robinson Descanse Lopez and Miguel Guimaraes who spoke particularly about the Amazon region in South America and some of the problems specific to that region in relation to climate change. Robinson Descanse Lopez is the Vice President of Climate Alliance and oversees the Amazon region in South America. I was startled to hear that 135 indigenous leaders and activists were killed in Colombia this year. In addition to this human loss of life, the fires in the Amazon rainforest have caused damage that is estimated to take over 1,000 years to repair. I think it was very impactful to hear of this situation from Mr. Lopez since he has been face to face with these issues.

I also found Mr. Guimaraes’ comments about the situation of indigenous people in Peru very insightful. One of the biggest issues for indigenous people in Peru is the legality of their land claims. Many indigenous groups in Peru have religious claims to the land they live on. These claims have not been respected by the Peruvian government. To make matters worse, the Peruvian government has granted rights to some of the land to different corporations who plan to develop the land.

It was also inspiring to learn about Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin (COICA) and the work that has been done regarding these issues. I am very much looking forward to meeting more inspiring individuals here at COP25.

Michael Goccia is a senior from Mystic, CT pursuing a dual degree in Management and Economics.

Who Do we Turn to when National Governments Fail to Lead?

Georgia Hernandez-Corrales – MS Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Since our arrival at COP@25, the message that impacted me the most was the prevailing need for communities to take part in the solutions to climate change. In addition, the governments need to start listening to the needs and demands of their own people in the face of environmental problems. People around the world have risen and are claiming their place in decision making. In the first day at COP@25, the islanders and coastal nations, indigenous leaders, and women gave a clear and forceful message about their position on climate change. It was really empowering to see these groups and representatives of their nations be direct about the demands that the affected countries must meet. This is because the most vulnerable nations and groups are the ones that are most severely affected, such as indigenous people, rural communities, women and the poor.

All these nations and social groups converge on the idea that climate change is a human rights issue. Conservation of the forests is a way to protect the environment, but also is a solution against poverty. Preventing deforestation allows for indigenous people to continue utilize the ecological services of the forest to provide for their needs. The fight against climate change can not only become an energy technological change, but must be fair to all the actors involved. The vision of “development” and of good living is different for each of these nations and groups, and they demand to be respected as a group with a different thinking of the world.

Dr. Wayne Walker presented a long-term study on land change from the Amazon basin. The results showed that the indigenous communities of the Amazon protected the forest from the continuous conversion of the land compared to sites outside their territories. Despite this, they are the people who are most affected by climate change and least recognized by government entities. For this reason, at COP@25 we heard the voices of native peoples calling attention to the countries involved in the bulk of CO2 emissions and the companies that destroy their forests. The assertion of indigenous populations is more important today than ever.

The Colombian lawyer and environmentalist (COICA), Robinson López, mentioned that the life of indigenous groups must be guaranteed. As well, their ancestral knowledge, their autonomy and governance, and the protection of the forest must be recognized and guaranteed. For me, the most shocking notice was knowing the number of environmentalists killed worldwide. Robinson also mentioned that 462 environmental leaders have been murdered in Colombia alone since 2016, but the same happens worldwide.

A change in the construction of socio-environmental solutions in local governments or even at the community level is a must. As Dr. Duchelle (CIFOR) mentioned, the new leaders in environmental matters must be the local governments. In the case that national governments go in the wrong direction, as in the case of the United States or Brazil, it is local governments that could make the good decisions.

We have to provide these communities the power of decision that was taken from them and support them in a way, so they are able to lead the change in their own communities. We can no longer support the oppression of vulnerable communities.

[Versión en español]

Desde nuestra llegada a la COP@25 el mensaje que más me impacto es la necesidad imperante de los pueblos y comunidades de tomar parte en las soluciones ante cambio climático. Además de que los gobiernos escuchen las necesidades y demandas de los pueblos ante las problemáticas medio ambientales. Los pueblos de todo el mundo se han levantado y están reclamando su lugar en la toma de decisiones. El día uno en la COP@25 fueron las naciones de los países de las islas y zonas costeras, líderes indígenas y mujeres que dieron el mensaje claro y contundente sobre su posición ante cambio climático. Fue realmente empoderador ver a estos grupos y representantes de las naciones ser directos sobre las demandas que los países desarrollados deben de cumplir. Esto debido a que son las naciones y grupos más vulnerables los que están siendo afectados más severamente, como lo son los pueblos indígenas, comunidades rurales, mujeres y los pobres.

Las diferentes naciones y grupos sociales convergen en que el cambio climático es un tema de derechos humanos. Conservar los bosques es una medida para conservar el ambiente, pero también para luchar contra la pobreza. La lucha contra el cambio climático no puede solo volcarse a un cambio en la tecnología energética, sino tiene que ser justa para todos los actores involucrados. La visión del “desarrollo” y del buen vivir es diferente para cada uno de estos pueblos, y todos, desde los pueblos indígenas hasta las comunidades costeras piden que se les respete su visión de mundo.

De los estudios a largo plazo sobre el cambio de uso del suelo que presentó el Dr. Wayne Walker, las comunidades indígenas de la Amazonía resguardan el bosque ante la continua conversión de la tierra en sitios ajenos a sus territorios. A pesar de esto, son los pueblos más afectados por el cambio climático y menos reconocidos ante entes gubernamentales. Es por lo que en la COP@25 se ha dado mucha importancia a la reivindicación de los pueblos originarios y están llamando la atención a los países que se ven involucrados en las emisiones de CO2 y compañías que destruyen sus bosques. La reivindicación de las poblaciones indígenas es hoy mas importante que nunca.

El abogado y ambientalista colombiano (COICA), Robinson López, mencionaba que a estos grupos indígenas se les debe garantizar la vida, la importancia de su conocimiento ancestral, se les debe respetar su autonomía y gobernanza, y reconocer la protección del bosque. Para mí lo más impactante fue conocer la cantidad de ambientalistas asesinados en todo el mundo. Robinson también mencionaba que sólo en Colombia desde el 2016 han asesinado a 462 líderes ambientalistas, pero lo mismo sucede en todo el mundo.

Un cambio en la construcción de soluciones socioambientales en los gobiernos locales o hasta a nivel de comunidad es necesario. Como mencionó la Dr. Duchelle (CIFOR), los nuevos líderes en materia ambiental deben ser los gobiernos locales. En el caso que los gobiernos nacionales vayan en la dirección incorrecta, como el caso de USA o Brasil, son entonces los gobiernos locales los que toman las buenas decisiones.

Estas comunidades deben tener el poder de decisión que se les fue arrebatado. No podemos seguir permitiendo que las comunidades más vulnerables sean oprimidas.

Georgia is a graduate student from the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Department at UCONN.

Questioning the Paradox of Sustainable Development

Mara Tu – BS Environmental Science and Urban and Community Studies

Day 1 and Day 2 of COP25 consisted of me struggling to process and understand this ever paradoxical idea of sustainable development.

Sustainable development — officially defined as “economic development that is conducted without depletion of natural resources”– is a core part of this climate change conversation as an investment space to act as a solution. Yet, in itself, development is synonymous to growth/creating more.

Sustainability is often-times just used as an add-on word and mechanism to soften the impacts of that development rather than to reverse and neutralize the effects. The cost of “development” has been ecological despair, loss of human lives and homes, and an ever-unpredictable and changing climate, so what about “sustainable” development makes it much different?

At the beginning of the week, my thoughts went to the extreme of questioning, what even is the point of all of these built structures and carbon emissions to get everyone here in Madrid? Is this just us continuing this culture and mindset of consumption while tricking ourselves into believing we are actually doing something? Where do you draw the line for development and creation of “new”, even if there are sustainability wins? Do these costs outweigh the benefits? Where do we put the accountability and pressure for most drastic changes?

Of course, in the context of international climate talks and agreements, it is incredibly unfair to deny the opportunity and process of development from developing nations. Since developed nations have been able to grow economically and heighten quality of life at the expense of the environment, poorer nations, and internal national inequity, there (hopefully) seems to be an understanding that developed nations must be the ones to make drastic changes, while developing nations can catch up. Yet, where is the line to be drawn? At what point do countries need to be evaluating if their development is sustainable (socially and environmentally) or even necessary? Do we, as developed nations, have the right to push sustainability into the development agendas of other nations?

For me, many of these questions followed after attending a panel event at the Moana Pacific Blue Booth. The event, titled “Maritime Boundaries & Climate Change in the Pacific: Shaping the Dialogue”, had incredible speakers: Prime Minister Hon. Henry Puna of the Cook Islands, Dr. Melchior Mataki from Solomon Islands, and Christelle Pratt, from the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat.

Most of the event discussions went into strategies on how large Pacific Ocean states are using technology to mark maritime borders as sea levels rise for their own economic and borders’ sakes but also in order to protect those waters as they have for centuries.

The moment that struck me the most was during the Q&A portion of the event, when a man from one of the Pacific large ocean states stood up to ask, “Everyone is always telling us as Pacific Islanders to conserve, conserve, conserve and protect our lands and waters, but I don’t understand why we cannot use our resources to grow economically?”.

There was a resentful and truly hurt tone in his voice. As there wasn’t enough time from the panelists to respond, I walked away feeling this man’s frustration and confusion as if my own question was left unanswered.

Highlighting this paradox of sustainable development, this man saw economic growth using resources on the islands as a way to improve the lives and status of people from the Pacific Islands. On the other hand, other people, perhaps even including some of the distinguished people on the panel themselves, see climate change as a reason to hold back from potentially exploiting resources and to protect what has remained.

Another COP25 event that left me weighing the costs and benefits of sustainable development was one I attended with a few other UConn@COP cohort members titled “Ecological Protection and Renewable Energy Transition in the Belt & Road”. During this event, the dangers of “sustainable development” and clashes between politics and true climate justice could be seen.

It had an odd assortment of panelist speakers; on one half, Chinese researchers talked about their solutions of promoting renewable energy along China’s Belt & Road trail, and on the other, representatives from the global NGO, Peace Boat explained their goals and new projects.

The Chinese Belt & Road Initiative was a global development strategy launched by Chinese President, Xi Jinping as a modern-day “Silk Road”. This initiative, started in 2013, includes investment and built infrastructure in more than 150 countries around the world, with hopes to build connections between China and the rest of the world.

On the speaking panel, researchers discussed different ways of implementing solar panels onto these plots of land that China has invested in and the potential benefits (including reducing desertification, increasing farming potential, providing clean energy, etc.). The scale at which China was looking to invest in renewables and opportunities to implement sustainable development in different countries along these trade routes was impressive.

However, all of this discussion about development came with a warning: during the Q&A part of the event, a Tibetan woman in the audience bravely stood up and faced the audience to remind them about what happened to Tibet. She said, “It all started with one road; then came the trucks and then the army and then the extraction of our resources”. She emphasized that it is important to get some knowledge of historical context as well as being wary that countries can use infrastructure as ways to advance their own means and neocolonialism.

The second portion of the panel event was dominated by Peace Boat. Peace Boat is an organization that uses a cruise ship, among many other programmatic projects, to bring people across the world together to promote peace, human rights, and sustainability. Driven by the Sustainable Development Goals from the UN, I was impressed with their mission and accomplishments but still a little taken aback by the need for the cruise ship, considering the environmental reputation they have. Even more shocking was the announcement of a new project, called “EcoBoat” that would be, as claimed, “the planet’s most environmentally sustainable cruise ship” with many cool new technological features and near-same uses as the Peace Boat.

While Peace Boat’s mission is admirable and no doubt has created unforgettable memories, educated thousands of people, and united people from around the world in a way like no other, I questioned if it was really worth the toxic waste, CO2 emissions, and marine disturbance from the ship.

The EcoBoat brought me even more skepticism. It wasn’t until after talking and really getting to know one of the staff members that I could at least understand where this NGO was coming from. While I still don’t believe there is a need for another cruise ship out on the sea, I admired that he truly believed in what he was doing. With his passion, I could only hope that he continues to do his work in a way that will benefit the greater good.

After a week of discussions and processing and hearing from people from all across the planet, I still haven’t completely concluded anything. But, I have had some takeaways about sustainable development. One, development will happen no matter what with economic profit as the ultimate driver of decisions: if not pushing for lower consumption, people must at least push for development to be as sustainable as possible. Two, developing nations have the right to figure out the best way and strategies for how they would like to go about development: developed nations should share the technology and research and resources for this without ill-will. Three, in general, it’s always important to question ourselves at some point in decision-making: ask ourselves, do we truly believe what we are doing is right and do the costs outweigh the benefits.

Mara Tu is a junior Environmental Science and Urban and Community Studies student in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Environmental Justice IS Social Justice

Natalie Roach – BS Environmental Sciences

When I was ten years old, my dream was to work at the World Wildlife Fund. I wanted to follow in Jane Goodall’s footsteps and save endangered species.

I made little business cards for myself with the panda logo on it and everything.

Over the years, I have grown away from that dream and towards other ones more focused on societies and social justice and food and people.

However I still have a soft spot in my heart for the World Wildlife Fund and everything it meant to me when I was younger – so when I saw the Panda Pavilion in the blue zone at COP, I was drawn to it.

In the midst of countries working their hardest to prove that they’re doing enough to stop climate change, the white and glass Panda Pavilion stood as a beacon of civil society and pure intentions. Well, more pure than other pavilions in the blue zone at least.

I ended up attending an event in the pavilion on oceans. It was a panel of scientists explaining the physical and biological impact of climate change on the body of water that covers 70% of our planet – plus the ambassador from the Seychelles, a small island in the Pacific Ocean that has begun feeling the effects of climate change.

While I learned some interesting facts about the ocean, the event overall was very frustrating. The Seychelles ambassador – a United Nations ambassador, a title that normally would get you a round of applause and excitement from any COP event – was not valued on the panel. His intro speech brought a completely different perspective to the panel, focusing on the cultural aspects and human implications of oceans. However, no one addressed or built off of what he said. None of the moderator’s questions were directed towards him. In fact, she asked a few questions about how small island nations are adapting to climate change, and actively directed them towards two other panelists. It seemed as though he was there solely as a way for them to check off the “island nations” box and not actually as a full participant.

I left feeling disappointed and unsure of my place. I’ve always had a passion for ecology – I’m majoring in environmental science – but I also have a passion for the human and social justice components of climate change and environmental degradation. This event was another example of how those two fields never seem to fit together.

Walking around the venue, I was even more sensitive to the fact that everything focused on reducing carbon emissions, and very little emphasis was placed on the plight of endangered species or the ecological solutions to climate change mitigation.

Then I ran into Danny, a fellow UConn@COP25 participant. He was looking similarly dejected – the COP can definitely be a lot to handle sometimes — and we ended up talking about what was going through our heads. Danny is someone who is also passionate about both ecology and social justice. He studies marine sciences and does research on turtles. I asked him how he was able to feel fulfilled in his studies when trying to balance these two fields, and he had a great answer about community and applying your knowledge.

This conversation reminded me that just because something doesn’t exist properly, doesn’t mean that I can’t do it – in fact, it usually is a sign that I really should do it if no one else will. It also reminded me of the importance of leaning on your people. I got more out of talking to Danny and other UConn@COP25 participants than I did from any event or lecture on the trip.

Later in the week, I had a great conversation with a woman from the World Wildlife Fund who ran an arm of the organization that focused on sustainable cities. They host international city contests and we had a passionate conversation about public transit. It turns out that, at least in some areas, the World Wildlife Fund is growing and expanding as well.

Natalie is from Cheshire, CT. She is an Environmental Sciences major with minors in Human Rights and Sustainable Food Crop Production. She will complete a Master’s in Public Policy in a fifth year as part of the UConn Fast Track Program.