On Dec. 4th, we posted a handful of blogs written by several of UConn’s first-ever group participants in the UN’s annual international climate summit. Today, we’re posting blogs from the second half of our stay, including a few overall reflections on what we observed in Paris and at COP21, and about the challenges of global action to address climate change. The following blogs include:

Seeing the Green Light at the End of the Tunnel: UConn @ COP21 Oksan Bayulgen

Lost in Translation: The Complexities of Reaching a Global Climate Agreement Kerrin Kinnear

On Gender and Climate Change Alexandra Mayer

The Climate Tradeoff: A Global Carbon Budget for the Future Andrew Carrol

UConn and the Climate Conference: Looking Ahead Ron Tardiff

COP21 Paris: All Hands on Deck for the next 20 years Anji Seth

Seeing the Green Light at the End of the Tunnel: UConn @ COP21

Oksan Bayulgen, Associate Professor, Political Science; Academic Director – Global House

What a week it was! Traveling to Paris on Monday with 12 students and 5 other faculty/staff to participate in the historic COP21, I did not know what exactly to expect from this experience. We did not have the authorized passes to observe the plenary sessions or even enter the ‘blue zone’ designated for some media and civil society observers. I did not know any of the students (except from their application materials), and I was going to spend a week with UConn sustainability staff and other faculty from different disciplines and with different research interests. Yet, the week turned out to be a huge success thanks to our trips to the many civil society events organized around the main conference and across the city, the enlightening and thought-provoking discussions we had every morning, and the close friendships we formed in just a matter of days. Of course the magical atmosphere of Paris helped as well!

What a week it was! Traveling to Paris on Monday with 12 students and 5 other faculty/staff to participate in the historic COP21, I did not know what exactly to expect from this experience. We did not have the authorized passes to observe the plenary sessions or even enter the ‘blue zone’ designated for some media and civil society observers. I did not know any of the students (except from their application materials), and I was going to spend a week with UConn sustainability staff and other faculty from different disciplines and with different research interests. Yet, the week turned out to be a huge success thanks to our trips to the many civil society events organized around the main conference and across the city, the enlightening and thought-provoking discussions we had every morning, and the close friendships we formed in just a matter of days. Of course the magical atmosphere of Paris helped as well!

I have two main insights from this week: one regarding the education of sustainability, particularly at UConn, and the other regarding the overall trends in climate change discussions. The wide scope of the events we attended as well as our morning discussions made obvious the importance of approaching climate change in a holistic manner. This is an interdisciplinary issue and looking at it through the prism of just one or two disciplines is limiting and unrealistic. The sources of, and solutions to, this crisis of humanity are found in the intersection of hard sciences, social change, human psychology, economics, human rights and politics. As such, we have a lot to learn from each other to find common and sensible solutions. At UConn we, as the faculty, need to engage in collaborative research and offer more courses that build on the strength of each of our disciplines as well as bridge the gap among them. We need to talk to and not past each other; we need to build research agendas that encompass sustainability and climate change topics as well as curricula that support general education of our students.

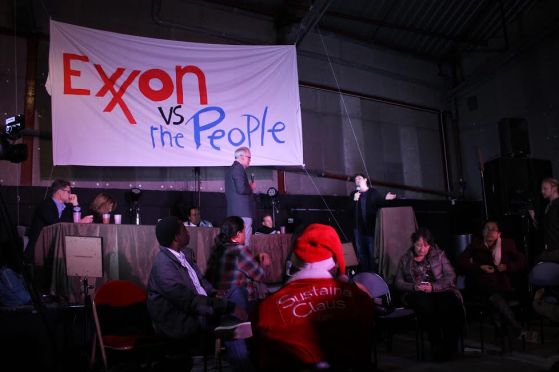

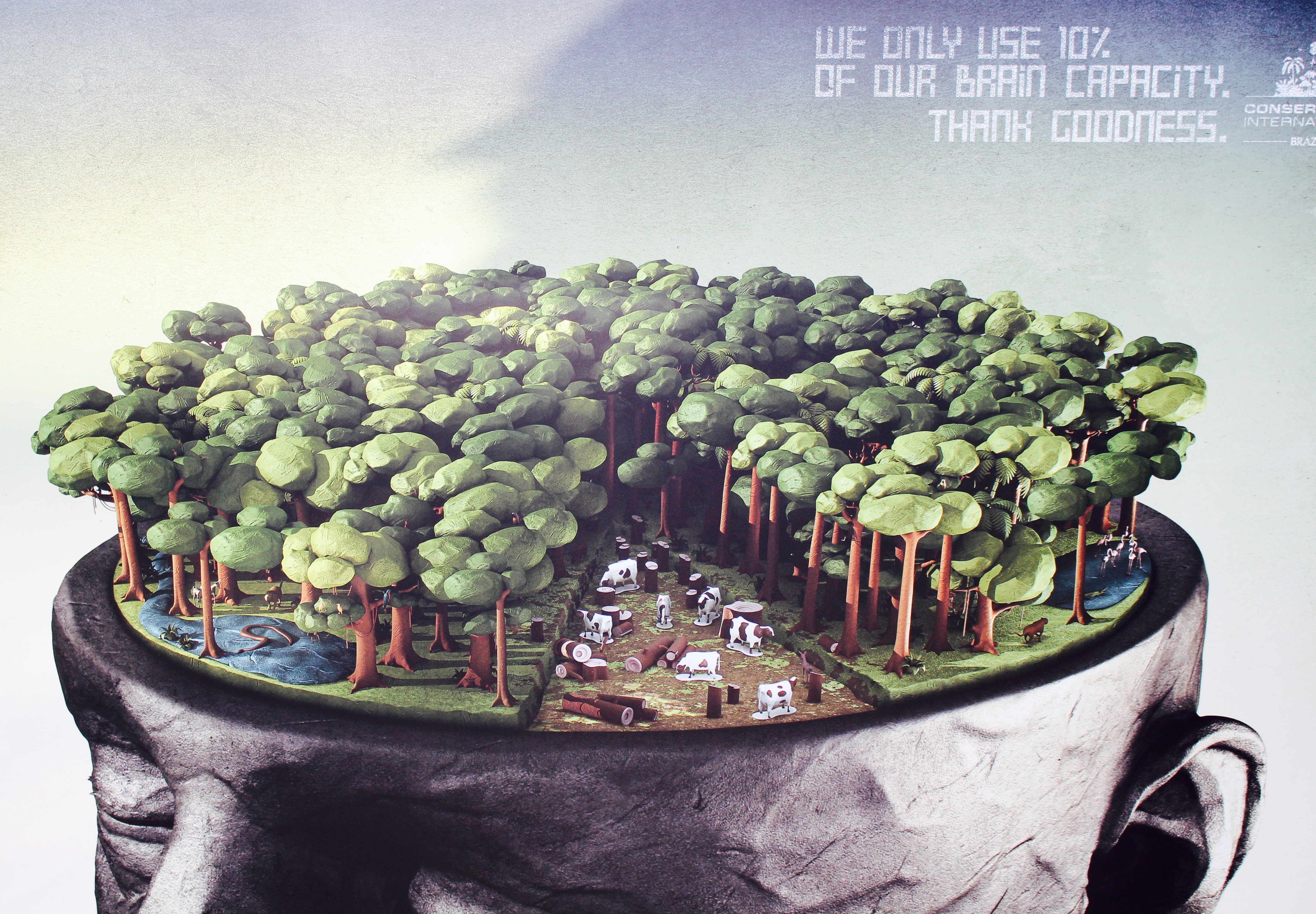

Regarding the broader discussion on climate change, it once more became clear to me that there are two counter trends in the world today. One is extremely positive and inspiring, as exemplified by the people and ideas in and around the COP21 conference. There are thousands of people who understand the urgency of the crisis and appreciate the environmental, social, economic and political consequences of not doing enough to reverse the trends. There is no questioning of the science. These are passionate, committed ordinary individuals, bureaucrats, non-governmental organizations and businesses who make personal and organizational sacrifices, utilize their entrepreneurial skills, and engage in fierce and determined activism. From the many booths at the COP21 Solutions displaying state-of-the-art and innovative technologies to the many panels on natural tropical forests, smart agriculture, indigenous peoples’ right to land in the Global Landscape Forum all the way to the 350.org’s mock trial of ExxonMobil at the outskirts of Paris, we saw progressive ideas and kindled spirits in defense of humanity and our planet. These are truly uplifting and promising developments.

Regarding the broader discussion on climate change, it once more became clear to me that there are two counter trends in the world today. One is extremely positive and inspiring, as exemplified by the people and ideas in and around the COP21 conference. There are thousands of people who understand the urgency of the crisis and appreciate the environmental, social, economic and political consequences of not doing enough to reverse the trends. There is no questioning of the science. These are passionate, committed ordinary individuals, bureaucrats, non-governmental organizations and businesses who make personal and organizational sacrifices, utilize their entrepreneurial skills, and engage in fierce and determined activism. From the many booths at the COP21 Solutions displaying state-of-the-art and innovative technologies to the many panels on natural tropical forests, smart agriculture, indigenous peoples’ right to land in the Global Landscape Forum all the way to the 350.org’s mock trial of ExxonMobil at the outskirts of Paris, we saw progressive ideas and kindled spirits in defense of humanity and our planet. These are truly uplifting and promising developments.

Yet, on the other side of the equation, we also observe the counter trends of denial, apathy, bureaucratic incompetency and gridlock, green washing, and political obstructionism. In the same week that the world leaders gathered in Paris to address climate change, in Vienna OPEC agreed to continue oil production uninterrupted, journalists have uncovered that fossil fuel companies have been spending billions of dollars hiding the truth about climate change, paying scientists to write expert reports questioning the urgency of climate change and even sponsoring certain parts of the very climate summit designed to shrink their industry. We have also heard many accounts of the difficulties inherent in international negotiations such as the one in Paris. The requirement of unanimity on the final terms of the agreement, the structural inequalities between developing and developed countries that raise questions about injustice and unfairness in the responsibility to pay for a cleaner environment, and the issues of sovereignty are all challenges facing a comprehensive, definitive deal. Perhaps the biggest challenge yet is the way COP21 is playing out in domestic politics. Just as the U.S. representatives are negotiating the details of the agreement and the U.S. president is projecting global leadership in addressing this crisis, some presidential candidates and congressional leaders back home are racing with each other to ridicule the efforts and threaten to reject the very terms that the U.S. delegation is busy negotiating at the conference. And, because of these troubling and depressing developments, there are legitimate concerns that the summit will fall short of its intended goals.

Despite the pendulum swinging back and forth from hope to despair, I believe (want to believe) that the tide is turning and the balance is shifting in favor of forces of change. The domestic and international momentum is finally here. Public opinion is changing, albeit slowly. Renewable energy technologies are becoming appealing to people not only on moral and environmental grounds but also in terms of economic benefits. Businesses that opt to become sustainable are being rewarded by consumers and see their profit margins increase. Many universities and municipalities are increasingly divesting their fossil fuel holdings. The list goes on and on… Against the dark forces, we, the educators and students, have to stand tall and unwavering in our principles and trust that the truth will prevail eventually. There is much more to do, but there is also light at the end of the tunnel! ACTION NOW!

Lost in Translation: The Complexities of Reaching a Global Climate Agreement

Kerrin Kinnear, OEP Intern

Muscles tensed by a mind overcome with frustration, I exit the auditorium. I had just witnessed a keynote address made by the President of COP21, Laurent Fabius, at the start of the Global Landscapes Forum. Arguably a once in a lifetime opportunity for an environmentalist, I had not understood a single word he said. Why? The speech was in French, and my language skillset is primarily limited to English.

Language issues are significant in the realm of global negotiation. Prior to traveling to Paris for the United Nations Climate Conference, most of my conversations about international climate action focused solely on which strategies were most appropriate for effectively mitigating fossil fuel emissions and adapting to the current and future impacts of climate change. Speaking with delegates from Madagascar and Namibia as well as negotiation observers from Dickinson University, I realized I had overlooked a key concept for the conference – the profound impact complexities of language can have on the effectiveness of international coordination.

With delegates and members of Civil Society from over 190 different countries gathered at COP21, ensuring a uniform sense of understanding is an incredible feat. To accommodate the resulting vast range of languages, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) mandates that all formal proceedings are interpreted into the organization’s six official languages: Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish. Using headsets, delegates from across the globe are able to hear live feeds of the negotiations in their preferred language, and contribute when they are given the floor. Representatives who speak none of the six official languages have the opportunity to speak in their language, so long as they pay for an interpreter to translate their message.

While this framework for communication demonstrates a certain commitment to universal comprehension, barriers still persist in the conference arena. During my conversation with Dickinson alumni, I was surprised to learn that a topic of debate for that day’s official proceedings was the clarification that international parties “welcomed” rather than “invited” countries to increase climate change efforts. From this, the importance of semantics and cultural word meanings in an international setting became evident. Additionally, when I spoke with a researcher from a French NGO focused on deforestation, he explained how quickly high-level jargon becomes integrated into the climate negotiations. As a result, delegates who have limited proficiency in the UN languages and who cannot afford interpreters struggle to keep up with and weigh in on complex conversations and policy strategies.

While this framework for communication demonstrates a certain commitment to universal comprehension, barriers still persist in the conference arena. During my conversation with Dickinson alumni, I was surprised to learn that a topic of debate for that day’s official proceedings was the clarification that international parties “welcomed” rather than “invited” countries to increase climate change efforts. From this, the importance of semantics and cultural word meanings in an international setting became evident. Additionally, when I spoke with a researcher from a French NGO focused on deforestation, he explained how quickly high-level jargon becomes integrated into the climate negotiations. As a result, delegates who have limited proficiency in the UN languages and who cannot afford interpreters struggle to keep up with and weigh in on complex conversations and policy strategies.

Despite the difficulties associated with communicating across languages, the United Nations and its member countries have held 21 climate change conferences and continue to plan global coordination on this issue. Because of the international community’s persistence in the face of cross-cultural communication barriers, I am more excited than ever before about the prospects for a global climate agreement.

On Gender and Climate Change

Alexandra Mayer

The agenda for the COP21 lists 22 steps towards agreement. Discussing “gender and climate change” is number 17. Women represent the majority of the world’s poor and agricultural workers and many are responsible for fetching water. Dramatic shifts in climate and food production are therefore primed to disproportionately harm women. Furthermore, women fight economic, social, and physical discrimination that also limit their ability to adapt to climate change.

Yet, on December 7th, Mary Robinson, former UN human rights chief and president of Ireland, lamented, “This [the UN conference] is a very male world. When it is a male world, you have male priorities,” and asserted, “women in developing countries are among the most vulnerable to climate change.” Her frustrated words indicate that there may be no legal text on gender equity coming out of the COP21 negotiations.

While I was listening to a panel discussion on indigenous and women’s rights at the Global Landscapes Forum in Paris, the man sitting next to me whispered, “Why should we care, if we’ll all be dead soon anyways?” alluding to the idea that if global warming goes unmitigated, humans may go extinct. I shushed the man to hear the speaker, but, as I have heard this argument used repeatedly to dismiss calls for human rights, I will reply now:

In fighting against climate change, you are fighting for the future of humankind. The next question, then, is what kind of future are you fighting for? We live in a beautiful world that is also riddled with atrocity, disparity, and exploitation.

Rape, racism, and domestic violence are global epidemics, so is poverty at the hand of the elite. I must ask, whose future are you fighting for when you rally to limit emissions, but not to stop the avoidable deaths that are occurring now at the hand of starvation, lack of health care, and violence? Are you okay with saving your own kind, and nobody else?

I know it is impossible to take on every injustice. We all have our own cause. Still, at the very least, I invite you to recognize the importance of human rights. Why should we save ourselves if we’ll only continue to disparage the earth and each other?

The Climate Tradeoff: A Global Carbon Budget for the Future

Andrew Carrol

While in Paris for the COP21 Conference during the first week in December, I had to make some rather mundane decisions, mostly confined to the breakfast buffet in our hotel: brie or gruyere, baguette or croissant? In contrast, the international negotiators in the Red Zone at Le Bourget are tasked with reaching consensus on a full plate of complex subjects: a global carbon budget, fossil fuel reduction, investment in renewable energy sources, and the tenuous balance of responsibility for carbon reductions. A topic that has been thoroughly discussed by many nations is a global carbon budget that would legally bind countries to a pre-determined level of carbon output set forth by the UNFCC. However, these plans have been squashed by nations that emit the most carbon. Thus, the cap-and-trade or cap-and-tax debate rages on across the ideological spectrum, from those who claim it’s our moral responsibility to those who maintain that a carbon budget would be unrealistic.

While in Paris for the COP21 Conference during the first week in December, I had to make some rather mundane decisions, mostly confined to the breakfast buffet in our hotel: brie or gruyere, baguette or croissant? In contrast, the international negotiators in the Red Zone at Le Bourget are tasked with reaching consensus on a full plate of complex subjects: a global carbon budget, fossil fuel reduction, investment in renewable energy sources, and the tenuous balance of responsibility for carbon reductions. A topic that has been thoroughly discussed by many nations is a global carbon budget that would legally bind countries to a pre-determined level of carbon output set forth by the UNFCC. However, these plans have been squashed by nations that emit the most carbon. Thus, the cap-and-trade or cap-and-tax debate rages on across the ideological spectrum, from those who claim it’s our moral responsibility to those who maintain that a carbon budget would be unrealistic.

As the UConn contingent discussed this concept more thoroughly, we were extremely like-minded about the idea of establishing a global carbon budget and taxing those who exceed their allowable emissions output. Even though we all supported a carbon budget, a few of us questioned its economic feasibility. I questioned whether the plan would disrupt the stability of international markets. And if the plan were to adversely affect the GDP of a country, would the carbon benefit and the value of this environmental externality outweigh the lost GDP? Will the bureaucracy and hierarchical nature of nations within the UN allow for such a plan to exist? What weights are given to additional factors, such as higher health care costs, the costs of shorter growing seasons, and even the potential for climate refugees?

As the UConn contingent discussed this concept more thoroughly, we were extremely like-minded about the idea of establishing a global carbon budget and taxing those who exceed their allowable emissions output. Even though we all supported a carbon budget, a few of us questioned its economic feasibility. I questioned whether the plan would disrupt the stability of international markets. And if the plan were to adversely affect the GDP of a country, would the carbon benefit and the value of this environmental externality outweigh the lost GDP? Will the bureaucracy and hierarchical nature of nations within the UN allow for such a plan to exist? What weights are given to additional factors, such as higher health care costs, the costs of shorter growing seasons, and even the potential for climate refugees?

When it comes to climate action, all factors need to be weighed in making a final decision. Unfortunately, the environment is usually second fiddle to the importance of economic stability. Yet, if we reach a breaking point in which we do not have a truly sustainable global environment, then the strength of a nation’s economy is meaningless. We cannot gamble on our environment – and we cannot put a price tag on a moral imperative.

UConn and the Climate Conference: Looking Ahead

Ron Tardiff

The 21st Conference of Parties (COP21) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change began in Paris, France on Nov. 30, and at the same time, a group of 18 UConn students, faculty, and staff traveled to Paris for five days to participate in a number of events surrounding the conference. The 12 students selected represented a diverse group of majors, most of which fall within the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, from marine sciences to human rights. For me, the conference was educational and sobering, but also inspired my fellow students and I to take action here at home.

Every day in Paris began with a group dialogue focused on the science or politics of climate change and solutions globally and at UConn. The diverse perspectives contributed by our multidisciplinary group of people definitely enhanced our conversations. The group visited the COP21 site in Le Bourget, Paris, and toured the public area of COP21, the Climate Generations Space. We also attended a networking night at the Kedge Business School co-sponsored by UConn and Second Nature, called “Higher Education Leads on Climate.”

On Friday, most of the group attended the Solutions COP21 exhibition, while I attended Oceans Day back at COP21. Oceans Day drew high-level attention to how the ocean and climate are inextricably linked. Among the many esteemed attendees were Prince Albert II of Monaco; Laurent Fabius, Foreign Minister of France and President of COP21; and Irina Bokova, the Director General of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.

As an American, one of the most sobering aspects of the conference and the international climate conversation in general is the skepticism towards U.S. commitment. Historically, particularly on climate change, the United States has failed to be a leader; if anything, we’ve often stymied the conversation. When I was at Oceans Day, I was asked by a French attendee whether I thought the U.S. would “follow through” this time. My only honest answer was that I believe our negotiators are working in good faith, but that the political climate – pun intended – at home is pretty unpredictable.

What is most interesting to me is that 190 countries convened to address an issue that an unfortunately large number of Americans refute entirely. This demonstrates how critical climate change education is. That is one of the many reasons our group will be advocating for a “sustainability” category to be included in General Education Requirements here at UConn.

Tackling global climate change epitomizes the types of challenges for which a liberal arts education aims to prepare students. The process of burning fossil fuels and forests and how that affects the climate is a fundamentally scientific issue. Why we continue these destructive processes, how these processes affect human civilization, and what we should do to improve our resilience and adaptation to climate change are intersectional issues spanning fields from science to the social sciences to humanities.

Now that we’re home, our group of “COP21ers” will be launching initiatives to improve our University’s carbon footprint, spearheading climate change conversation at UConn, and creating works of art, writing, or media to highlight the impacts of climate change. And we’ll be advocating for a greater role of sustainability education in the curriculum at UConn. We’ll be using the new perspectives we gained from meeting so many people from around the world to help UConn be a leader in this quintessentially global issue.

COP21 Paris: All Hands on Deck for the next 20 years

Anji Seth, Associate Professor, Geography

“Welcome to those who are working to save our planet”

“Later will be too late”

“We can’t tell our children we didn’t know”

“The world is in our hands”

“7 Billion people, one planet”

Billboards across Paris, in Charles DeGalle airport, in metro stations, and on historic buildings, reminded us constantly why we were there. Our group of 12 students and 6 faculty/staff from UConn were on a mission to learn about and participate in the historic events taking place, as UN Envoys and negotiators work on an international agreement that would limit global warming to [2C][1.5C]*. This is the 21st UN Conference of the Parties, or COP21.

Billboards across Paris, in Charles DeGalle airport, in metro stations, and on historic buildings, reminded us constantly why we were there. Our group of 12 students and 6 faculty/staff from UConn were on a mission to learn about and participate in the historic events taking place, as UN Envoys and negotiators work on an international agreement that would limit global warming to [2C][1.5C]*. This is the 21st UN Conference of the Parties, or COP21.

More than 20 years ago the United Nations agreed to “talk” about Global Warming. The road to Paris has been long and the stars are now aligning for an international agreement to “act”. The scientific evidence is overwhelming and indisputable, global leaders have been educated and show some understanding of the threats to nations, people and ecosystems, and people across the planet are calling for action. Clearly those who deny the science are on the wrong side of history. The final agreement to act from the Paris 2015 COP21 will not be perfect, there should be a review process in place to further reduce emissions over time, but the agreement will be a starting point for action over the next 20 years.

We traveled to Paris with a 12 students from across the UConn colleges, each passionate about their discipline and the global context in which they will make their marks. During the last 20 years global warming has been in the realms of climate-related sciences, economics and policy, the next 20 years there will be a role for everyone.

Implementation of the Paris agreement will require artists and engineers, teachers and health professionals, ecologists, attorneys and business leaders. The careers of UConn students will follow the implementation of the Paris agreement over the next 20+ years. Today’s students will be in the driver’s seat for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, implementing carbon pricing, adapting local infrastructure, and assisting ecosystems in need.

These are exciting times. Let’s get to work.

*[brackets] indicate items under negotiation.

One thought on “Thoughts from Paris”

Comments are closed.