The Brundtland Report, released by the UN's World Commission of Environment and Development in 1987, regards sustainability as the action of “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.”

As we pursue sustainability, we must recognize that it has not yet met the needs of the Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in our communities. In order to move forward, we must address the historical exploitation of Black, Brown, low-income, and marginalized people in order to make sustainability equitable.

This webpage aims to highlight the intersections of environmental justice, social justice, and UConn’s strategic sustainability goals, as well as to provide educational resources for those interested in learning more.

Header image: Climate Justice Initiative Mural Design © City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program Climate Justice Initiative / The Art Circle: Denise Bright Dove Ashton-Dunkley, Eurhi Jones, Gamar Markarian, and Dolores Stanford with the Climate Justice Initiative Collaborators.

A climate justice-approach to sustainability recognizes that the climate crisis is a social justice issue rooted in the systemic exploitation of low-income individuals, communities of color and Indigenous Peoples. Colonial-capitalist expansion in pursuit of resource accumulation displaces Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands, topples ecological balances, and creates a global power imbalance in access to clean air and water, food, and decent livelihoods (Agyeman et al., 2003; Dunbar-Ortiz, 2014; Goodyear-Kaopua, 2009).

What is Environmental Justice?

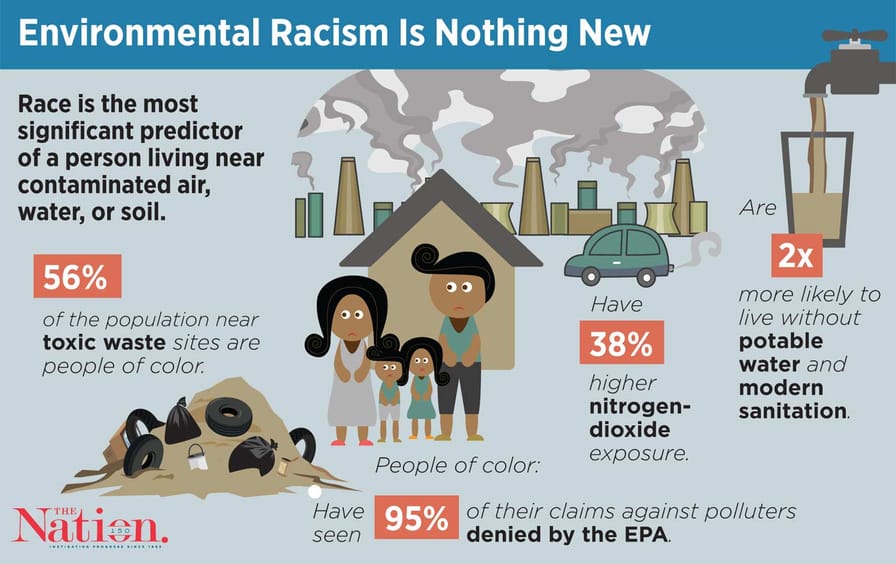

Environmental justice address long-standing prevalent issues of living quality for low-income, Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities. The Environmental Justice (EJ) movement was notably sparked by protests condemning the 1982 dumping of toxic waste materials in Warren County, North Carolina. Sit-ins, protests, and marches were ultimately unsuccessful, but caused environmental justice activists to recognize a pattern: “Pollution-producing facilities are often sited in poor communities of color.”

The common phrase "Not in my Back Yard" (NIMBY) was born from wealthy neighborhoods rejecting sites in their neighborhoods through legal means, while lower-income communities lacked funds for such defenses (and access to information that would raise alarm). For these reasons, large corporations, regulatory agencies, and local planning/zoning boards often are left to designate polluting sites to poor communities of color for development.

Climate change may feel like a far-away problem, but it is an omnipresent concern. U.S. winters have become milder and spring has come earlier. In the future, we can continue to expect less snow, more frequent precipitation as rain, and increased coastal flooding. Heat waves will become more severe and frequent, as will hurricanes.

Severe heat waves not only affect the habitats of wildlife, but also contribute to poor air quality which exacerbates pre-existing health conditions in urban areas. Suitable habitats for invasive species and vector-borne diseases, like Lyme disease, will shift further north affecting unfamiliar communities (CT Physical Climate Science Assessment Report | CT Institute for Resilience & Climate Adaptation (CIRCA)).

The PSEG Power up Connecticut LLC coal power station in Bridgeport, CT (pictured left). Coal power plants release hazardous gaseous chemicals (such as carbon monoxide) into local air, which can exacerbate respiratory issues.

Racial, social, and environmental injustices do not affect communities equally. Many BIPOC (Black [people], Indigenous [peoples], and People of Color) have been prevented from: moving to certain neighborhoods (Redlining, outlawed by the 1968 Fair Housing Act), fairly voting in local and national elections (voter suppression), accessing fresh and affordable food (Food Apartheid), and accessing affordable, safe healthcare (Racism in Medicine). Examining each phenomenon separately, we see how environmental injustice is pervasive in our society.

The MIRA Incinerator is located in Hartford, CT, where nearly two thirds of the population are BIPOC individuals and a third of the city's population suffers from poverty. Low-income communities of color are disproportionately located near industrial pollution-producing facilities which contribute to respiratory-related illness and water quality issues.

People of color, especially Black individuals, have been constrained to live in urban communities where they experience high levels of industrial pollution and exacerbated heat (urban heat island effect).They are discouraged from voting for many reasons, including but not limited to the inaccessibility of polling locations and times. BIPOC in urban settings may also be unable to access nutritious food, ultimately leading to health issues like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Even hospital care brings adverse treatment by medical professionals who have internalized stereotypes about the pain tolerance, mental health, and biology of their patients.

Redlining map of New Haven and surrounding cities during the 1930s (pictured left). While ruled illegal by the 1970 Fair Housing Act, Black and Latinx Americans continue to be denied mortgages at higher rates than their white counterparts in many metropolitan areas of the country.

Using our voices is a powerful way to support the environmental justice movement. Practicing allyship can take many forms, including advocating for more inclusive and equitable spaces, as well as acknowledging and valuing the socio-environmental knowledge possessed by BIPOC (NRDC). By listening to and collaborating with individuals from all backgrounds, we ensure that nobody is left out as we address the environmental threats facing our society.

As we students, educators, and members of society at large begin to practice allyship and have discussions regarding inclusive environmentalism, it is crucial that positionality is recognized in each issue. Reflecting on our relationship with the environment - what we stand to lose as the impacts of climate change worsen - helps us move away from performative allyship. In doing so, the microphone is passed to BIPOC to discuss their lived experiences with the environment and injustice. Rather than giving BIPOC a seat at the table, which implies ownership of the table, passing the mic signifies a respect for their lived experiences and cultural knowledge. Everyone deserves to speak for themselves, and fostering respectful communication must include a mutual effort to listen to voices without gatekeeping.

Key Definitions

- Environmental Justice: addresses environmental racism by necessitating involvement of BIPOC voices in environmental spaces. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice as "the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies." Including two different definitions of environmental justice is intended to highlight the evolving nature of the topic and the voices dictating the conversation.

- Environmental Racism: the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on people of color due to systemic racism.

- POC: Person of Color. An acronym that relays the communities often marginalized on the basis of race and ethnicity.

- BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. An acronym that relays the communities often marginalized on the basis of race and ethnicity, with emphasis on the historical mistreatment of Black and Indigenous populations. (UN's meaning of Indigenous)

- Latinx: relating to people of Latin American origin or descent. Latinx is used as a gender-neutral or non-binary alternative to Latino/a; some individuals prefer the term Latine.

- Intersectionality: a lens through which you can see the places where power structures collide, interlock, and intersect. The term was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1993. (Gloria Walton & SCOPE)

- Intersectional Environmentalism: an inclusive version of environmentalism that advocates for both the protection of people + the planet. It identifies the ways in which injustices happening to marginalized communities and the earth are interconnected. It brings injustices done to the most vulnerable communities, and the earth, to the forefront and does not minimize or silence social inequality.

Resources

Explore some resources developed and hosted by UConn students and staff to better understand and participate in environmental justice initiatives.

Environmental Justice Toolkit

UConn graduate Himaja Nagireddy ('20) created the Environmental Justice Toolkit during her undergraduate career as a way to teach others about environmental justice. She used her experiences in the UConn@COP (COP25) program and ongoing research to provide an opportunity for others to take action to support the environmental justice movement.

World Wide Climate Justice Teach-In 2022

Watch the 2022 Teach-In for Climate Justice, hosted by the Offices of Sustainability at UConn and Southern Connecticut State University. The event, titled "Climate Justice Across Scales in Connecticut," was an interactive panel discussion on climate justice issues across state and local levels.

Environmental Justice Word Bank

This helpful word bank provides definitions for some terms commonly used in Environmental Justice conversations. All definitions are subject to change as language is constantly evolving!

Environmental Justice in the United States

Certain communities are buffered from impacts of climate change more than others. Storrs, CT is the one of the Safest Places to Avoid Natural Disaster in the country, but other communities are more vulnerable. (Our conversation here centers on climate change in the United States. We recognize that this list is not exhaustive, but rather emphasizes limited environmental struggles within the United States.)

Income inequality and the lasting impacts of redlining drive many BIPOC families to cities where they frequently experience environmental racism/discrimination. The rising temperatures we expect from climate change will make urban areas even warmer due to concrete and heat-absorbing building materials. This effect, combined with air pollution, significantly lowers air quality, leading to higher prevalence of respiratory and cardiovascular disease. Income inequality and other barriers to affordable care makes healthcare a costly (or impossible) burden for many. Read Urban Heat Island Management Study, Texas Trees Foundation.

Contiguous United States

UConn Land Acknowledgement Statement

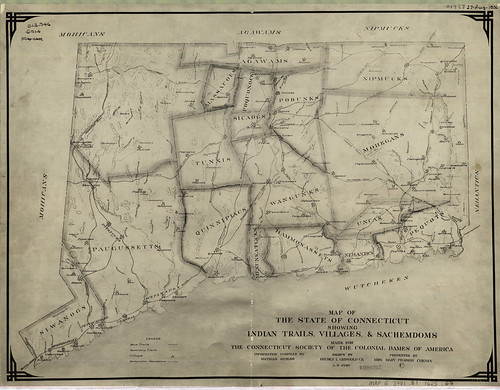

"We would like to begin by acknowledging that the land on which we gather at UConn is the territory of the Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Nipmuc, and Lenape Peoples, who have stewarded this land throughout the generations. We thank them for their strength and resilience in protecting this land, and aspire to uphold our responsibilities according to their example."

Some individuals prefer Indigenous or Native American - read more here.

Native American tribes and lands have been exploited by European colonizers for centuries, which has fueled environmental justice movements in the United States. Historical case studies reveal how economic vulnerability is often linked to natural resource extraction, a consequence which often yields additional socioeconomic and environmental harm (i.e. lead poisoning from extraction of minerals, military weaponry testing, and waste disposal). Light is also being shed on the climate injustice Native American communities are faced with. Tribes contribute minimal greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions yet face some of the gravest effects of global warming such as food insecurity, water shortages, and legal battles for control of tribal resources.

The Keystone pipeline runs through the American Midwest and a significant portion of tribal land; Pipelines are a consistent threat to ecosystems, drinking water sources, and public health, especially for Indigenous communities. In 2018 the Trump administration had been sued by two Native American communities for failure to conduct an environmental impact survey and violating historical treaty boundaries. *Two years later, in 2020, their suit proved successful in revoking the pipeline’s operating permit.

The American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands are all territories of the United States that are frequently left out of conversations surrounding climate change and environmental injustice. All islands are experiencing sea level rise firsthand, which threatens the contamination of their groundwater supply and could dislocate countless communities.

While contributing minimal emissions on a global scale, Puerto Rico has experienced intensified, slower moving hurricanes - take a look at impact of the 2017 Hurricane Season. Hurricanes like Maria and Irma have cut off the island’s water supply, electricity, and cellular service, and cost Puerto Rican lives - both directly and through poor emergency storm response/lacking federal aid.

In the state of Hawai’i, Native Hawaiians and other marginalized populations are located close to Oahu’s landfills and the Kahe power plant. These polluting facilities have been linked to the high asthma rates and cancer found in surrounding communities. In addition, vog (volcanic smoke) and noxious emissions released by lava flows threaten indigenous communities that have been displaced to hazardous areas by Western Colonizers.

- Environmental Justice for Asians and Pacific Islanders

- Pacific Northwest, Alaska & The Islands (video contains content from many regions of the United States as well as island territories and indigenous communities.)

Support for BIPOC Individuals and Allies + UConn Community Resources

View resources below for bias reporting, mental and general health services, and community engagement.

Institutional Equity

- Conduct, speech, or expression that "negatively targets, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group due to race, ethnicity, ancestry, national origin, religion, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age, physical, mental, and intellectual disabilities, as well as past/present history of mental disorders" can be reported to the Division of Student Life & Enrollment Office of Community Standards at the link below. Visit the Community Standards webpage to learn more about reporting and for other important information such as phone numbers and offices with which incidents are shared.

- The UConn Office of Institutional Equity (OIE) focuses on office accountability and legal investigations. They administer UConn’s non-discrimination policies, ensure compliance with state and federal laws/regulations related to equal opportunity and affirmative action (including Title IX). Click here for resources from OIE.

- The UConn Office of Diversity and Inclusion (ODI) focuses on providing professional development opportunities related to as well as educational resources for students and faculty. They facilitate trainings, in partnership with the OIE, tailored towards improving faculty awareness of Unconscious Bias and Cultural Competency. Click here for resources from ODI.

Mental and General Health Services at UConn

Check out the links below for information about UConn's mental and general health services available to students.

- Diversity & Inclusion Resources: Intersections of Health and Racism

- UConn Psychological Services Clinic provides mental health services to individuals of all ages in the area. They are operated by the University of Connecticut as a training clinic for graduate students in Clinical Psychology. Services are provided by graduate students under the supervision of licensed clinical psychologists and faculty members in the department of Psychology.

- SHaW (Student Health and Wellness) Mental Health Services provide clinical services to promote the emotional, relational, and academic potential of all students at the University of Connecticut.

- UConn’s Cultural Centers have resources to support the social, behavioral, and cultural needs of students. They provide a safe space for underrepresented populations at UConn and are a reference for issues and historical context related to particular communities. Visit each center's website for more information on how to get involved and how to stay in contact with the centers.

External Mental Health Services

- The Loveland Foundation - Therapy Fund for Black Women and girls

- Therapy for Black Men - Directory of Black Male Mental Health Practitioners

- Therapy for Black Girls - Directory of Black Female Mental Health Practitioners

- National Queer and Trans Therapists of Color - Mental Health Practitioner Directory

- Inclusive Therapists - a "social justice and liberation-oriented mental health directory, community, and resource hub"

Other External Resources

Anti-Racism Resources:

You can use these resources below to learn more:

- University of Washington Library | Racial Justice Resources: Race, Nature & the Environment

- Yale Environment360 Journal | Unequal Impact: the Deep Links Between Racism and Climate Change

- Brené with Ibram X. Kendi on How to Be an Antiracist

Additional Resources:

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- EPA Environmental Justice

- DEEP Environmental Justice

- EPA | Timeline of the Environmental Justice Movement

- Second Nature Statement | There is No Climate Justice Without Racial Justice

- AASHE (The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education) | Racial Equity & Social Justice Resources

Additional resources you’d like to see on this page? Contact us at: sustainability@uconn.edu